Note: You can watch my presentation based on this research from the 2021 Ancestral Health Symposium here, watch a much longer video that covers missing slides and answers questions about the talk here, download a PDF of my slides here, and see a short list of minor corrections to the presentation in note 1.

In a rush? Skip to the conclusions here.

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, we already knew that vitamin D helps reduce the risk of respiratory infections, especially when given to people who are deficient.1 We also knew that it helps us make antimicrobial peptides, and that it simultaneously boosts our immune system’s ability to fight viruses and bacteria while dampening the excessive or dysfunctional activities of our immune system that can lead to autoimmune disease.2

Nevertheless, it didn’t automatically follow from this that vitamin D would reduce the risk of COVID-19. Viruses regularly hijack good things within our bodies to use them against us. It is therefore entirely possible a virus could hijack things made with the help of vitamin D and use those things against us.

One of the very first things we learned about SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is that it enters human cells by binding to a human protein known as ACE2.3 From the perspective of human physiology, ACE2 is an enzyme that supports healthy blood pressure, cardiovascular function, and respiratory function.4 From the perspective of the virus, ACE2 is a “receptor” that it can use as an easily opened door, allowing it to enter our cells. This is a great example of the virus hijacking something that is very health-promoting in order to cause disease.

Binding to ACE2 is a property that SARS-CoV-2 shares with only two other coronaviruses — the first SARS virus5 and human coronavirus NL63,6 a virus that mainly infects children and immunocompromised people7 — but not with the coronaviruses8,9 or rhinoviruses10 that cause the common cold, and not with the viruses that cause the flu.11 Animal studies prior to the pandemic had generally shown that vitamin D increases the amount of ACE2 on the cell surface,12–14 (note 2) raising the concern that vitamin D could make it easier for the virus to enter our cells. Moreover, since most viruses that cause respiratory infections do not use ACE2 to get into cells, this raised the possibility that the existing research showing vitamin D protects against respiratory infections may not apply to COVID-19.

Because of this, my initial response to the ACE2 research in March of 2020 was to urge caution against supplementing with vitamin D. I wrote that we should continue to get sunshine and eat vitamin D-rich foods, such as fatty fish, but should avoid supplementing or at least limit supplements to 1700 IU per day.

Others, such as Dr. Rhonda Patrick of Found my Fitness, argued in April of 2020 that vitamin D’s ability to raise ACE2 might actually make COVID-19 less severe, since ACE2 protects against lung damage. My response to this was to point out that a moderate increase in ACE2 might offer moderate protection against lung injury, but since viruses grow exponentially, the same moderate increase in ACE2 might lead to an exponential increase in viral load.

Dr. Patrick also pointed out circumstantial evidence that poor vitamin D status contributed to severity: COVID-19 hospitalization rates were higher in obese people, African Americans, Somali immigrants in Sweden, and older people, all of whom have lower vitamin D status. While vitamin D is a plausible way to tie these together, I pointed out that other factors, such as hypertension, could explain the cluster just as well. Thus, the circumstantial evidence at that time was relatively easy to dismiss.

Things slowly began to change toward the end of April, 2020. At a country level, COVID-19 mortality was associated with northern latitudes where it is more difficult to get vitamin D from the sun.15 On April 23 and April 29, the first two studies emerged from South and Southeast Asia tying low vitamin D status in individual COVID-19 patients to more severe disease and greater mortality.16,17

Additional ways that vitamin D could protect against the disease were also becoming more clear over time. Low lymphocytes, high neutrophils, and high levels of interleukin-6 emerged as key predictors of poor outcomes,18–24 and existing research suggested vitamin D had the potential to help with all three.25–29

As more and more research emerged, in a series of posts, I slowly began to change my mind and become convinced that vitamin D is effective against COVID-19, possibly dramatically so.

Unfortunately, the first three studies directly tying the vitamin D status of individual patients to COVID-19 outcomes, all from South or Southeast Asia and all originally published between April 23 and May 5, 2020, have since been retracted, with no explanation why.16,17,30 In fact, there is reason to doubt that the authors of the second paper, which came out of Indonesia, even exist. In July of 2020, a group of Indonesian physicians and medical professors claimed to look everywhere within the Indonesian medical system without ever finding these authors.31 They lamented that this potentially fraudulent paper created an “infodemic” of “misinformation” about the supposedly helpful effects of vitamin D that had spread like wildfire on Twitter and Reddit.

Fast forward to August of 2021,(note 3) and these retracted papers are just three drops in what is quickly becoming an ocean of legitimate research. There are now 98 observational studies,32–129 6 published randomized controlled trials,130–135 and dozens more randomized controlled trials that are registered and are either not yet started, underway, or completed but not yet published.

Let us now take a look at what that research has found, starting with the observational studies.

Observational Studies: The Pooled Results

The pooled results of the observational studies136–138 suggest that people with vitamin D deficiency have somewhere between a 2-fold and 5-fold increased odds of getting infected with COVID-19, having a severe case, and dying.

Click here for a much more detailed look at the pooled data.

Correlation does not necessarily mean causation. These data do not tell us that poor vitamin D status causes poor COVID-19 outcomes. They don’t, on their own, tell us that maintaining good vitamin D status prevents poor COVID-19 outcomes. To look at that, we need to look at the randomized controlled trials. Before we do that, however, there are important insights we can glean by looking at specific observational studies.

The Association Is Similar in Children

Studies done specifically in pediatric cases show that children are five times more likely to have a severe case if they are deficient in vitamin D.139

Population-Level Vitamin D Status Explains Global Disparities in COVID-19 Outcomes

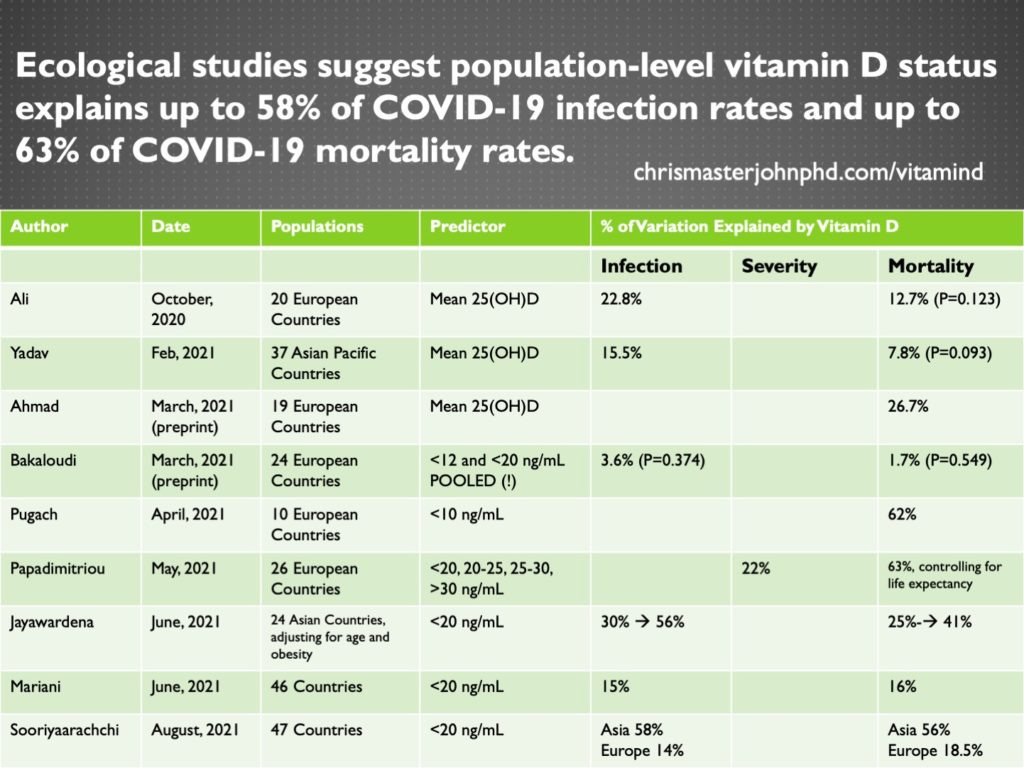

Studies that look at predictors and outcomes in populations rather than individuals are called ecological studies.

Since COVID-19 and any other disease occurs in individuals rather than populations, these are among the worst types of studies to try to understand cause and effect. However, since population characteristics determine how well infectious diseases spread, ecological studies are interesting: if poor vitamin D status within a population leads to a higher infection rate in that population, it could be because more vulnerable people make the virus spread more easily. Moreover, from a public health perspective, if countries with high rates of vitamin D deficiency have worse outcomes, policymakers should consider efforts to reduce vitamin D deficiency as a means of fighting the pandemic.

Nine ecological studies63,64,109–115 found that population-level vitamin D status explains up to 58% of the infection rate and 63% of the mortality rate.

The results of all nine studies are summarized in the table below:

The one study that did not find an association pooled together rates of deficiency that were defined in some countries as <12 ng/mL and in other countries as <20 ng/mL.115 This caused a serious loss of precision by defining deficiency in different ways for different countries.

The three studies that used the mean vitamin D status of a population rather than the prevalence of deficiency64,112,114 arrived at some of the lowest estimates. Mean vitamin D status is not a very good metric, because it is the people who are deficient who are at the highest risk, and a country can have good mean vitamin D status despite a high prevalence of deficiency simply by having a lot of people with high vitamin D status that bring up the average.

Of the eight studies that found an association, those with the highest estimates either defined vitamin D deficiency by the more stringent 10 ng/mL cutoff,63 considered four different categories of vitamin D cutoffs separately while controlling for life expectancy,110 or controlled for age and obesity.111

Since the studies that had greater precision and controlled for other key drivers of COVID-19 mortality came to the highest estimates, it seems that the higher estimates are probably more accurate, and that population-level vitamin D status may explain up to 58% of the variation in infection rates and is likely to explain about 60% of the variation in mortality rates remaining after age, life expectancy, and obesity rates are taken into account.

Blood Levels: Where is the Danger Zone?

Five studies examined the ability of vitamin D status to act as a blood marker that could predict severity95 or death.51,87,88,91

When looking for a good biomarker, we want it to be sensitive and specific. Sensitivity refers to our ability to avoid false negatives: we want to find as many of the people who are going to have a severe case or die as we can. Specificity refers to our ability to avoid false positives: we want to avoid telling people they are going to get a severe case or die when they won’t. Studies that perform these analyses look for a cutoff for vitamin D status that optimizes for the balance of these two characteristics: where do we get the most sensitivity without sacrificing too much specificity, and the most specificity without sacrificing too much sensitivity?

These studies arrived at cutoffs between 9 ng/mL and 25 ng/mL.

Sensitivity ranged 59-82% and specificity ranged 56-72%. So, vitamin D status will correctly predict the risk of severity or death in roughly half to two-thirds of cases.

These cutoffs don’t represent the point at which you are fine as long as you stay above them. They represent the real danger zone, where you can predict that someone has a pretty decent chance of having a severe case if they get infected, or of dying if they develop a severe case.

9-25 ng/mL is a pretty broad range of cutoffs. We need more of these types of studies to more precisely identify the top of the danger zone. However, if the top of the danger zone seems to lie somewhere between 9 and 25 ng/mL, then caution warrants assuming that 25 ng/mL may represent the high end of the danger zone and steering clear of it by maintaining vitamin D status considerably higher than this.

As it stands, the bottom of the normal range is already 30 ng/mL. So, just staying in the normal range keeps us away from the danger zone.

What About 40-60 ng/mL or Even Higher?

Very few people in most of these studies have vitamin D status higher than 40 ng/mL.

One incredible exception is a study of every Quest Diagnostics patient in the United States who had vitamin D status measured in the year leading up to the pandemic and had at least one COVID test.74 Although this study was retrospective, the vitamin D status came before the COVID tests, and if people had multiple COVID tests they were counted as infected if any one of them turned up positive. This allowed us to go back in time and essentially look forward to see the vitamin D status predicting the future risk of infection.

This study had 191,779 subjects, including 4,016 people with 55-59 ng/mL and 8,305 people with greater than 60 ng/mL. Infection risk was almost 13% in those with the lowest vitamin D status and around 6% in those with the highest. For every 1 ng/mL of vitamin D status, the relative risk of infection went down 2%, and it bottomed out around 55 ng/mL. After controlling for age, sex, race, latitude, and the season of the vitamin D measurement, vitamin D status explained 96% of the remaining risk of getting infected.

This study suggests that 50-60 ng/mL is the best range to be in to have the lowest infection risk.

Nevertheless, just as infection risk remains 6% in this range, being in this range does not guarantee anyone will not wind up in the hospital or even die.

One study in Germany62 had seven patients with vitamin D status over 45 ng/mL, and five of them were hospitalized.

Another study of hospitalized patients in the UK106 had about seven patients in the 40-60 ng/mL range. They, like everyone else in the study, were hospitalized, although none of them went to the ICU.

Between March 1 and May 8 of 2020, during the peak of the pandemic in New York City, 25% of patients admitted to the Mount Sinai Health System — about 65 patients — had vitamin D status over 40 ng/mL, and roughly 30% of them died.107

A study of hospitalized patients in Iran85 provided a vague hint that risk may actually increase when vitamin D is in the toxic range: although only seven patients had vitamin D status over 100 ng/mL, two of them died, bringing their mortality rate (29%) closer to the patients with less than 10 ng/mL (36%) than to those with 10-100 ng/mL (19%). Due to the small number of people in this range, these results are not statistically significant, but they urge caution to stay out of the toxic range, something good to do anyway.

Overall, these studies support maintaining vitamin D status in the 50-60 ng/mL range to achieve the lowest risk of infection, but not regarding this as any kind of panacea that can guarantee a mild or non-fatal case.

The Importance of Measuring Parathyroid Hormone (PTH) and Calcitriol

There are three major vitamin D-related markers we want to look at in the blood:

25(OH)D is a marker of the supply of vitamin D, and is what I have been referring to above as “vitamin D status.”

Calcitriol acts on the vitamin D receptor (VDR) within our cells to regulate the expression of our genes, and it reflects the biological activity of vitamin D.

Elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) is the signal that our body perceives the biological activity of vitamin D as deficient.

We may be able to create a fourth:

25(OH)D does, contrary to most reviews and textbooks, activate the vitamin D receptor and carry out biological activity just like calcitriol; it is less powerful, but it is present in higher concentrations.140,141 As we learn more about the relative biological activities of each of these compounds, we may be able to create a “biological activity” index from their respective concentrations in the blood.

Click here for a brief introduction to these markers if you are unfamiliar with them.

Two studies103,129 emphasize the importance of measuring PTH and calcitriol. These studies cast doubt on how easily we can interpret all the other studies in which these two markers were not measured.

In 348 patients hospitalized in Italy,103 those with 25(OH)D less than 12 ng/mL and normal PTH did not have any higher risk of hypoxemic respiratory failure. In fact, they had a slightly lower risk that was not statistically significant. Those with elevated PTH had an increased risk, however, and those who had increased PTH and D less than 12 ng/mL had the highest risk of all:

Although the slightly lower risk of the patients with normal PTH and D less than 12 ng/mL (second bar compared to fourth bar) is not statistically significant and we should place no serious confidence in it, could it be that their 25(OH)D levels were a little lower because they were converting more of it to calcitriol, gaining higher biological activity, and that this is why their PTH was normal? If so, their slightly lower risk may reflect their immune system’s slightly greater access to biologically active vitamin D.

Indeed, the second study emphasizes the importance of calcitriol over 25(OH)D. In 26 patients within a German ICU,129 25(OH)D had no relationship to any markers of severity except that those with adequate levels had higher concentrations of plasmablasts, which are cells that are on their way to become antibody-producing B cells. However, patients with low calcitriol levels had worse transfer of oxygen from their lungs to their blood, faster deteriorating health on an index used to predict the risk of death, and required longer periods of time on mechanical ventilation.

These two studies emphasize three important points:

In studies that fail to find a relationship with 25(OH)D, measuring PTH and calcitriol may reveal a central importance of vitamin D metabolism that would otherwise be overlooked.

While some portion of having high 25(OH)D reflects having good vitamin D supply, we can never be certain what portion of it reflects poor synthesis of calcitriol. This by itself could explain why some people with high levels of 25(OH)D still wind up dying of COVID-19 even though the bulk of people with higher levels have a greatly reduced risk.

What we should actually be looking for is biological vitamin D activity, and this is probably best represented by some kind of index we need to develop from a calculation of both the 25(OH)D and the calcitriol, and by measuring PTH, which reflects the body’s own perception of whether the biological vitamin D activity is adequate.

Having COVID-19 Depletes Vitamin D Status

Two studies suggest that having COVID-19 itself depletes vitamin D status:

Among a series of Spanish ICU patients,108 the proportion of patients with 25(OH)D greater than 20 ng/mL dropped five-fold from 17.6% to 3.2% after just three days of being in the ICU.

In a subset of patients hospitalized in Italy who had a record of pre-COVID vitamin D status,103 mean 25(OH)D dropped 42% from 21 ng/mL to 12 ng/mL by the time they were admitted to the hospital.

This is not surprising. Vitamin D has been known for years to be a negative acute phase reactant,142 which means that 25(OH)D declines acutely in response to the onset of inflammation.

Is this an argument against protective causality?

Not at all!

The reason 25(OH)D declines during the onset of inflammation is because it is used to activate immune cells to mount a response against infection.

The fact that 25(OH)D drops in response to inflammation does raise the possibility that low vitamin D is the effect of poor COVID-19 outcomes rather than the cause, but it does nothing more than that. It isn’t an argument against vitamin D being the cause of poor COVID-19 outcomes. These two possibilities are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they are both completely compatible with each other and with a central role for vitamin D in protecting against COVID-19: low vitamin D status means less vitamin D available for the immune response, and yet the immune response uses up whatever vitamin D is available, making it even lower. Indeed, we know from the Quest Diagnostics study of almost 200,000 people74 that poor vitamin D status in the year before the pandemic is associated with a greater risk of infection during the pandemic.

Nevertheless, to truly address cause-and-effect relationships, we must turn to the randomized controlled trials.

The Two Most Important RCTs: Entrenas-Castillo (Spain) and Murai (Brazil)

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the most important type of evidence to review when asking the question of whether improvements in vitamin D status cause protection against COVID-19. Since participants are allocated to vitamin D treatment or control randomly, the better vitamin D status of the treatment group cannot be said to be caused by better COVID-19 outcomes, or by confounding factors that correlate with people’s beliefs, choices, and behaviors. Additionally, since participants are allocated randomly, confounding factors that may alter COVID-19 outcomes unrelated to vitamin D should be roughly evenly distributed between the groups, especially if the trial is large.

The Cochrane Library’s “living systematic review” of vitamin D and COVID-19 RCTs143 will likely indefinitely remain the most important analysis of this evidence in the peer-reviewed literature. It is called a “living” review because it aims to be updated and republished any time that new RCTs might change the basic conclusions.

The most recent edition of this review was published in May, and it included three RCTs.130–132 One of them from Northern India looked at the effect of vitamin D on the ability of mild and asymptomatic cases to clear the virus within three weeks.132 Since the primary endpoints of the Cochrane review are mortality, hospital admissions, disease severity, and quality of life, this paper was discussed briefly but largely ignored in favor of the other two trials done in hospitalized patients.

Thus, the current incarnation of the Cochrane review is a showdown between two trials:

The Entrenas-Castillo trial130 was done in Spain and tested the effect of oral 25(OH)D on ICU admissions and mortality.

The Murai trial131 was done in Brazil and studied the effect of oral vitamin D on length of hospital stay, ICU admissions, and mortality.

These two trials used very different approaches:

The Entrenas-Castillo group treated 76 patients with the standard of care at the time (azithromycin, hydroxychloroquine, and, if needed, a broad-spectrum antibiotic) and randomized them to treatment with 25(OH)D or control. 25(OH)D in an oral preparation is known as calcifediol. The treatment was 0.532 mg the first day, and 0.266 mg on days 3 and 7, and once a week thereafter. This bypasses the need for the liver to convert vitamin D to 25(OH)D so it is not the same as giving oral vitamin D. However, if we were to convert the doses into oral vitamin D equivalents, it would be 106,400 IU on day 1, and 53,200 IU on days 3 and 7 and once a week thereafter. The decision to send people to the ICU was made by a blinded committee, and all data was collected and analyzed by blinded scientists, but control patients were not given placebos and the treating physicians had access to the patient’s electronic health record, where it was recorded if they were in the treatment group.

The Murai group randomized 240 patients with respiratory distress and/or serious comorbidities to a single dose of 200,000 IU of oral vitamin D or a placebo. It was double-blind.

The two trials also came to very different results:

In the Entrenas-Castillo trial, 50% of the control group but only 2% of the vitamin D group required ICU treatment. There were 2 deaths in the control group and none in the vitamin D group. Calcifediol treatment reduced the odds of ICU admission by 98% (P<0.001).

In the Murai trial, there was no effect of vitamin D on the length of hospital stay, ICU admission, or mortality.

Because these two trials are so different in their methodology, the Cochrane group did not pool their data, try to compare and contrast them, or even try to choose between their conflicting results to hold one or the other trial up as more reliable. Instead, it described each of them in detail, and then ran each of them separately through an algorithm designed to determine the risk of bias associated with each trial for the review’s primary endpoints.

The Murai trial was rated as “low risk of bias” for all the main endpoints, while the Entrenas-Castillo trial was rated “of some concerns” for risk of bias for mortality and ICU admissions.

The concern about mortality was that the protocol for the study stated that mortality would be followed up over 28 days, whereas the final paper did not state how long the patients were followed up for. This raised the concern that they might have changed the length of time for which the patients were followed up. Since there were only two deaths in the trial and no statistical analysis could be performed on mortality, however, this ultimately doesn’t impact the conclusions of the trial. The main outcome of the trial is the 98% reduced odds of ICU admission.

The other concern, which did impact ICU admissions, was that the paper reported that some “nonmasked specialists” had access to the list of who was in what treatment group and the paper doesn’t make clear what their role was. This concern makes sense but we must keep in mind that the decisions to send people to the ICU were made by a blinded committee and the data was collected and analyzed by blinded investigators.

There are some very important distinctions between the two trials that are not discussed in the Cochrane review and suggest that the difference in results was due to real biological differences in the treatments rather than in differences in their risk of bias:

In the Entrenas-Castillo trial, treatment was started on day 7 of symptoms, on the same day as hospital admission, and none of the patients were said to have required oxygen at the start of the trial. They didn’t measure the vitamin D status of their patients, but average vitamin D status in that region of Spain during that time of year is 16 ng/mL. The oral 25(OH)D would maximize blood levels of 25(OH)D within five hours.144

In the Murai trial, treatment was started on day 10 of symptoms, and on average 1.4 days after hospital admission. Respiratory distress was a major inclusion criterion, and 90% of the patients required oxygen support before vitamin D treatment was started. A single oral dose of 100,000 IU takes five days to maximize blood levels of 25(OH)D.145 This trial used 200,000 IU, which is likely to take even longer. There are also some indications that inflammation impairs the ability of the liver to convert vitamin D to 25(OH)D,146,147 suggesting that these patients would have taken considerably longer than five days to convert the supplement to 25(OH)D since they were suffering from serious inflammation. We know from the study that 25(OH)D was increased at the time of hospital discharge, which was, on average, seven days after the trial started.

Thus, the Entrenas-Castillo trial maximized 25(OH)D on day 7 of symptoms, day 1 of hospital admission, and possibly prior to anyone needing oxygen support. The Murai trial maximized 25(OH)D at some unknown timepoint likely between day 15 and day 17 of symptoms, up to one full week after most of the subjects already needed oxygen support. The success of the Entrenas-Castillo trial and the failure of the Murai trial are thus easily explained by the Entrenas-Castillo trial maximizing 25(OH)D 8-10 days earlier in the course of illness.

Two authors from MIT and Harvard published a mathematical analysis of the Entrenas-Castillo trial148 that provide additional reasons to believe the results are genuine effects of the treatment:

While the P value was reported in the paper as <0.001, the exact P value is more than 1000 times smaller than this at 0.00000077. This is important because at the time the trial was published, there were 500 other COVID-19 trials registered. Random chance would be expected to cause at least one of these trials to generate spurious results with a P value of 0.002, and could plausibly generate spurious results at a P value of 0.001. However, it is completely implausible that one of these trials would generate spurious results at P=0.00000077.

Although the trial is small, the chances that comorbidities would be unevenly distributed in a way that would produce the results observed is 1 in 60,000. The large effect size overcomes the small sample size, and this is reflected in the high statistical significance shown by the exceedingly low P value.

The patients received their treatments as a supply of pills from a nurse. In theory, they could deduce which group they were in by talking to each other and counting the number of pills they were getting, but that seems unlikely to happen very often. The treating physician would be able to see in the electronic health record whether the patient was getting 25(OH)D, which is more plausible. However, in order for this bias to lead to the level of statistical significance found in this study when the genuine results would not have been statistically significant at P<0.05 would require that every one of the patients and doctors figured out who was getting what treatment, and that this led the doctors to supply data to the blinded ICU committee that was so biased that it made them double the rate at which control patients were sent to the ICU and or halve the rate that vitamin D patients were sent there. This seems exceedingly implausible on all counts.

The results of the Entrenas-Castillo trial are strengthened by observational studies of the same protocol applied more broadly in Spanish hospitals:

When the protocol was authorized at five out of eight hospital wards, among 838 patients treated in the wards, the treatment was associated with 87% fewer ICU admissions and 70% fewer deaths.149

Among 537 patients in five hospitals, 79 received this treatment and it was associated with 78% fewer deaths.90

Thus, the showdown between the Entrenas-Castillo and Murai trials suggests the Entrenas-Castillo protocol is effective because it raises 25(OH)D rapidly early enough in the course of illness, whereas the Murai trial failed because it raised 25(OH)D only when it was too late.

There are four other RCTs published, none of which are quite as important as these two, but which generally either have little to say, or offer further support for the effect of vitamin D. Before we finish, let’s take a look.

Four More RCTs

The first of these four trials was from Northern India and was included in the Cochrane review although covered in much less detail.132 Forty individuals who tested positive but were asymptomatic or had mild cases were given 60,000 IU per day of oral vitamin D. On day 7, if they achieved 50 ng/mL, the treatment was reduced to once a week. If not, it was continued daily throughout the second week. The treatment tripled the proportion of people who cleared the virus by week 3 from 20.8% to 62.5%.

The other three trials are less impressive.

In 42 mild patients from Mexico,133 10,000 IU per day for 14 days increased mean 25(OH)D from 20.2 to 28.2 ng/mL and the prevalence of people with greater than 20 ng/mL from 18.2% to 31.2%. At day 7, 20% of the controls but none of the vitamin D patients had more than three symptoms.

These results sound good on the surface, but they aren’t very convincing, because the authors asked the same question four different ways: Did they have any symptoms? Did they have more than one? Did they have more than two? Did they have more than 3? Only the more-than-three version was statistically significant and there were actually slightly more people in the vitamin D group who had any symptoms at all. The authors didn’t adjust for making multiple comparisons, so with four questions they basically had a one in five chance of one of them being spuriously statistically significant. While these results aren’t very convincing, the treatment wasn’t very impressive anyway: by the end of the study almost 70% of the treatment group still had 25(OH)D lower than 20 ng/mL!

10,000 IU per day is just not enough without a loading dose if you are trying to raise 25(OH)D very quickly in someone with poor status.

In another trial, 69 Saudi Arabian patients with mild symptoms were randomly assigned to receive either 5,000 IU per day or 1,000 IU per day of vitamin D for two weeks.134 Dry cough resolved 42% faster (6.2 days vs 9.1 days) in the higher-dose group and loss of taste resolved 33% faster (11.4 days vs 16.9 days). As with the previous study, these results are less convincing than they sound at first, but this study is even worse. They looked at 11 different symptoms, didn’t make any adjustments for making so many comparisons, and picked the two that were significant. More to the point, at the end of the study the 25(OH)D was 25 ng/mL in the higher-dose group and 24 ng/mL in the lower-dose group! There is no way on earth 1 ng/mL could have produced a meaningful impact on symptom resolution.

The results of these last two studies suggest that doses between 1,000 IU and 10,000 IU per day are meaningless without a loading dose when you need to raise vitamin D status quickly.

The last trial, published in Nature Scientific Reports,135 randomly assigned 87 subjects in India with mild to moderate illness to 60,000 IU per day of oral vitamin D or control. The dose was continued for eight days for normal-weight subjects and ten days for overweight subjects. 25(OH)D went from 17 to 89 ng/mL. This study purports to show that inflammatory markers associated with poor COVID-19 outcomes — C-reactive protein, lactate dehydrogenase, interleukin-6, ferritin, and the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio — were reduced by vitamin D treatment. However, the vitamin D group had much higher inflammatory markers at baseline, and at the end of the trial, although they were lower than at the beginning, they were still non-significantly higher than in the placebo group.

While this may have reflected a true effect of vitamin D, it is completely indistinguishable from a statistical artifact known as regression to the mean. After physicists discovered that what goes up must come down, statisticians discovered that high numbers tend to come down while low numbers tend to come up, and that really high numbers tend to come down a lot, while really low numbers tend to come up a lot. That is, things that diverge from the mean tend to regress back to the mean. The cure for this is to compare the ending values in an RCT between the treatment and control groups. Since those ending values were not significantly different, this study does not show us anything we can clearly distinguish from chance.

Altogether, these four studies show the following:

1,000 IU, 5,000 IU, and 10,000 IU are all relatively useless doses without a loading dose when they are started after someone has become ill.

60,000 IU per day might reduce inflammatory markers, although the latter finding is not convincing because the trial failed to evenly distribute inflammatory markers between the two groups at baseline.

60,000 IU per day does convincingly speed viral clearance.

None of these four trials are as important as the first two, because they deal with asymptomatic patients or mild to moderate patients and do not look at serious consequences such as hospitalization, ICU admission, or mortality.

Conclusions From the RCTs

Altogether, the Entrenas-Castillo protocol reigns supreme, because it is one out of two trials that examined the impact of vitamin D on serious endpoints in hospitalized patients, and its success can be attributed to the biological superiority of its approach: when someone is seven days into illness, vitamin D deficient, and facing acute inflammation, high-dose oral 25(OH)D is needed to rapidly raise the blood levels.

60,000 IU per day supports more rapid viral clearance in mild and asymptomatic cases, but lower doses have not yet shown any convincing effects.

Interactions With Other Nutrients

None of these studies took into account the interactions vitamin D has with other nutrients, yet these interactions are critical.

In at least some contexts, vitamins A and D cooperate together to support the immune system. Spiesman showed in 1941 that vitamins A and D prevented the common cold when given together, but that each did little on their own.150

Vitamin A itself had become known as the “anti-infective” vitamin in the 1920s,151 and cod liver oil — rich in both vitamins A and D — had been used to treat tuberculosis in the 1800s, and was shown effective against the common cold, bedside fever, and measles in clinical trials performed in the 1920s and 1930s.152 While the early view was that vitamin A was the anti-infective agent within cod liver oil, Spiesman’s later results suggested that vitamins A and D were equally important.

Vitamins A and D cooperate with each other to produce a protein known as MGP that is activated by vitamin K, especially vitamin K2, to protect blood vessels from becoming calcified.153–155 Vitamin A levels are depleted in severe COVID-19 cases,156 and MGP is more poorly activated — suggesting the vitamin K status of the blood vessels is poorer — in COVID-19 cases compared to healthy controls and in people with more severe cases compared to more mild cases.157

Although vitamin E may not participate as directly in the production and activation of specific proteins with the other three fat-soluble vitamins, all four of them share some common pathways of metabolism, and vitamins A, D, and K all have the potential to deplete vitamin E levels.158–160

Zinc is needed to produce the vitamin D receptor and to allow it to bind to DNA and regulate gene expression.161–163 Magnesium, even more broadly, is needed for every step of vitamin D metabolism and function.164 Evidence that either mineral specifically protects against COVID-19 is currently limited, but a report of four cases suggested that high-dose zinc lozenges help speed recovery.165

None of these studies provide clear evidence that these nutrients need to be co-supplemented with vitamin D for it to be effective against COVID-19, but they provide proof of principle that they are needed at some level for optimal function of vitamin D, and they emphasize the need to study their interactions with vitamin D in the context of COVID-19.

In my personal opinion, each 10,000 IU of vitamin D should be matched with 5-10,000 IU of vitamin A (as retinol), 200 micrograms of vitamin K2 (ideally as a mix of MK-4 and MK-7), and 20 IU of alpha-tocopherol in a background of naturally occurring mixed tocopherols and tocotrienols. The combination of dietary and supplemental magnesium should at least meet the RDA, and zinc status should be maintained on the higher end of normal. I have previously written an extensive article on zinc dosing available here.

Biological complexity is like an onion: you peel back each layer and all you get is the next layer. As such, it is important to maintain the diet adequate in all nutrients when trying to get benefit from any particular nutrient. Vitamin D ultimately requires adequacy of all nutrients in at least some indirect way, so we should also aim to prevent any deficiencies while trying to harness the benefits of vitamin D for COVID-19.

Overall Conclusions

Synthesizing all of the data, we can conclude as follows:

While the threat of COVID-19 persists, actively maintaining 25(OH)D in the 30-60 ng/mL range is likely to protect against getting infected, with the best protection offered in the 50-60 ng/mL range.

Whether a supplement is needed to maintain this and how much depends on one's environment, lifestyle, diet, and other factors, so it is best to measure the blood level. Many people living in temperate regions would require 5,000 IU per day during the coldest half of the year.

Maintaining D in this range will also prevent a 5-or-more-day delay in the ability to quickly raise 25(OH)D with vitamin D supplements upon getting sick.

If the Entrenas-Castillo protocol is adjusted for the relative bioavailability of 25(OH)D and vitamin D and converted into the equivalent of oral vitamin D3 supplements, it translates to 106,400 IU on day 1, 53,200 IU on days 3 and 7, and 53,200 IU per week thereafter until symptoms resolve. If this is in turn translated into daily dosing, it would be the equivalent of 30,400 IU per day for the first week, followed by a maintenance dose of 7,600 IU per day until symptoms resolve. This could be simplified to a loading dose of 200,000 IU once, followed by a 10,000 IU per day maintenance dose until symptoms resolve.

This protocol should be started at the first sign of any possible symptom and should not be delayed until COVID-19 is confirmed. This is needed to raise biological vitamin D activity at the beginning of the infection, rather than waiting until it is a) too late and b) too difficult to raise 25(OH)D in an environment of excessive inflammation.

For someone who is maintaining 25(OH)D in the 50-60 ng/mL range, the loading dose might be unnecessary. However, for anyone with 25(OH)D lower than this, the loading dose is critical. For someone who is likely deficient at the time of infection and waits until diagnosed or hospitalized before starting vitamin D, it is imperative for a physician to prescribe calcifediol (that is, oral 25(OH)D) at a dose of 0.532 miligrams on day 1, followed by 0.266 milligrams on days 3 and 7, and weekly thereafter until symptoms resolve.

Although concrete evidence for this is lacking, my personal opinion is that each 10,000 IU of vitamin D (the loading dose can be excepted from this) should be matched with 5-10,000 IU of vitamin A (as retinol), 200 micrograms of vitamin K2 (preferably as a mix of MK-4 and MK-7), and 20 IU of alpha-tocopherol in a background of naturally occurring mixed tocopherols and tocotrienols. The diet should be analyzed (for example, as described here) to make sure that no nutrients are deficient and zinc dosing as described here should be considered.

More Content Like This

Subscribe to my COVID-19 Research Updates list here.

Watch my Ancestral Health Symposium presentation on this topic:

Watch my “live watch party” where we watched the AHS presentation as a community, and I interjected with some of the slides I had to skip due to time in the original presentation, and answered questions from the live chat:

Read my other posts on vitamin D and COVID-19 here and here.

Read my previous articles on COVID-19 here.

See all my content on vitamin D here.

Join the Next Live Q&A

Have a question for me? Ask it at the next Q&A! Learn more here.

Subscribe

Subscribe or upgrade your subscription here.

Join the Masterpass

Masterpass members get access to premium content (preview the premium posts here), all my ebook guides for free (see the collection of ebook guides here), monthly live Q&A sessions (see when the next session is here), all my courses for free (see the collection here), and exclusive access to massive discounts (see the specific discounts available by clicking here). Upgrade your subscription to include Masterpass membership with this link.

Learn more about the Masterpass here.

Take a Look at the Store

At no extra cost to you, please consider buying products from one of my popular affiliates using these links: Paleovalley, Magic Spoon breakfast cereal, LMNT, Seeking Health, Ancestral Supplements. Find more affiliates here.

For $2.99, you can purchase The Vitamins and Minerals 101 Cliff Notes, a bullet point summary of all the most important things I’ve learned in over 15 years of studying nutrition science.

For $10, you can purchase The Food and Supplement Guide for the Coronavirus, my protocol for prevention and for what to do if you get sick.

For $29.99, you can purchase a copy of my ebook, Testing Nutritional Status: The Ultimate Cheat Sheet, my complete system for managing your nutritional status using dietary analysis, a survey of just under 200 signs and symptoms, and a comprehensive guide to proper interpretation of labwork.

References

1. Martineau AR, Jolliffe DA, Greenberg L, et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory infections: individual participant data meta-analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2019;23(2):1-44. doi:10.3310/hta23020

2. Sassi F, Tamone C, D’Amelio P. Vitamin D: Nutrient, Hormone, and Immunomodulator. Nutrients. 2018;10(11). doi:10.3390/nu10111656

3. Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Guo Y, Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367(6485):1444-1448. doi:10.1126/science.abb2762

4. Turner AJ, Hiscox JA, Hooper NM. ACE2: from vasopeptidase to SARS virus receptor. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25(6):291-294. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2004.04.001

5. Li F, Li W, Farzan M, Harrison SC. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science. 2005;309(5742):1864-1868. doi:10.1126/science.1116480

6. Fehr AR, Perlman S. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1282:1-23. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-2438-7_1

7. Abdul-Rasool S, Fielding BC. Understanding Human Coronavirus HCoV-NL63. Open Virol J. 2010;4:76-84. doi:10.2174/1874357901004010076

8. Wentworth DE, Holmes KV. Molecular determinants of species specificity in the coronavirus receptor aminopeptidase N (CD13): influence of N-linked glycosylation. J Virol. Published online 2001. https://journals.asm.org/doi/abs/10.1128/JVI.75.20.9741-9752.2001

9. Owczarek K, Szczepanski A, Milewska A, et al. Early events during human coronavirus OC43 entry to the cell. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):7124. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-25640-0

10. Novick SG, Godfrey JC, Godfrey NJ, Wilder HR. How does zinc modify the common cold? Clinical observations and implications regarding mechanisms of action. Med Hypotheses. 1996;46(3):295-302. doi:10.1016/s0306-9877(96)90259-5

11. Lu R, Müller P, Downard KM. Molecular basis of influenza hemagglutinin inhibition with an entry-blocker peptide by computational docking and mass spectrometry. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2015;24(3-4):109-117. doi:10.1177/2040206615622920

12. Xu J, Yang J, Chen J, Luo Q, Zhang Q, Zhang H. Vitamin D alleviates lipopolysaccharide‑induced acute lung injury via regulation of the renin‑angiotensin system. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16(5):7432-7438. doi:10.3892/mmr.2017.7546

13. Lin M, Gao P, Zhao T, et al. Calcitriol regulates angiotensin-converting enzyme and angiotensin converting-enzyme 2 in diabetic kidney disease. Mol Biol Rep. 2016;43(5):397-406. doi:10.1007/s11033-016-3971-5

14. Cui C, Xu P, Li G, et al. Vitamin D receptor activation regulates microglia polarization and oxidative stress in spontaneously hypertensive rats and angiotensin II-exposed microglial cells: Role of renin-angiotensin system. Redox Biol. 2019;26:101295. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2019.101295

15. Rhodes JM, Subramanian S, Laird E, Kenny RA. Editorial: low population mortality from COVID-19 in countries south of latitude 35 degrees North supports vitamin D as a factor determining severity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51(12):1434-1437. doi:10.1111/apt.15777

16. Alipio M. Vitamin D Supplementation Could Possibly Improve Clinical Outcomes of Patients Infected with Coronavirus-2019 (COVID- 2019). Published online 2020. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3571484

17. Raharusuna P. Patterns of COVID-19 mortality and vitamin D: an Indonesian Study. Published online 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3585561

18. Wang W, Liu X, Wu S, et al. Definition and Risks of Cytokine Release Syndrome in 11 Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients With Pneumonia: Analysis of Disease Characteristics. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(9):1444-1451. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiaa387

19. Liu J, Li S, Liu J, et al. Longitudinal characteristics of lymphocyte responses and cytokine profiles in the peripheral blood of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. EBioMedicine. 2020;55:102763. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102763

20. Wan S, Yi Q, Fan S, et al. Characteristics of lymphocyte subsets and cytokines in peripheral blood of 123 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (NCP). bioRxiv. Published online February 12, 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.02.10.20021832

21. Pedersen SF, Ho Y-C. SARS-CoV-2: a storm is raging. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2202-2205. doi:10.1172/JCI137647

22. Chen G, Wu D, Guo W, et al. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2620-2629. doi:10.1172/JCI137244

23. Herold T, Jurinovic V, Arnreich C, et al. Elevated levels of IL-6 and CRP predict the need for mechanical ventilation in COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(1):128-136.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.008

24. Liu T, Zhang J, Yang Y, et al. The role of interleukin-6 in monitoring severe case of coronavirus disease 2019. EMBO Mol Med. 2020;12(7):e12421. doi:10.15252/emmm.202012421

25. Wu H-X, Xiong X-F, Zhu M, Wei J, Zhuo K-Q, Cheng D-Y. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on the outcomes of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18(1):108. doi:10.1186/s12890-018-0677-6

26. Tabatabaeizadeh S-A, Avan A, Bahrami A, et al. High Dose Supplementation of Vitamin D Affects Measures of Systemic Inflammation: Reductions in High Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein Level and Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) Distribution. J Cell Biochem. 2017;118(12):4317-4322. doi:10.1002/jcb.26084

27. Rodriguez AJ, Mousa A, Ebeling PR, Scott D, de Courten B. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on inflammatory markers in heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):1169. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-19708-0

28. Wang Y, Yang S, Zhou Q, Zhang H, Yi B. Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on Renal Function, Inflammation and Glycemic Control in Patients with Diabetic Nephropathy: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2019;44(1):72-87. doi:10.1159/000498838

29. Miroliaee AE, Salamzadeh J, Shokouhi S, Sahraei Z. The study of vitamin D administration effect on CRP and Interleukin-6 as prognostic biomarkers of ventilator associated pneumonia. J Crit Care. 2018;44:300-305. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.08.040

30. Glicio E. Vitamin D level of mild and severe elderly cases of COVID-19: a preliminary report. Published online 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3593258

31. Henrina J, Lim MA, Pranata R. COVID-19 and misinformation: how an infodemic fuelled the prominence of vitamin D. Br J Nutr. 2021;125(3):359-360. doi:10.1017/S0007114520002950

32. Meltzer DO, Best TJ, Zhang H, Vokes T, Arora V, Solway J. Association of Vitamin D Deficiency and Treatment with COVID-19 Incidence. medRxiv. Published online May 13, 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.05.08.20095893

33. Hernández JL, Nan D, Fernandez-Ayala M, et al. Vitamin D Status in Hospitalized Patients with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(3):e1343-e1353. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgaa733

34. Im JH, Je YS, Baek J, Chung M-H, Kwon HY, Lee J-S. Nutritional status of patients with COVID-19. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;100:390-393. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.08.018

35. Ye K, Tang F, Liao X, et al. Does Serum Vitamin D Level Affect COVID-19 Infection and Its Severity?-A Case-Control Study. J Am Coll Nutr. Published online October 13, 2020:1-8. doi:10.1080/07315724.2020.1826005

36. Luo X, Liao Q, Shen Y, Li H, Cheng L. Vitamin D Deficiency Is Associated with COVID-19 Incidence and Disease Severity in Chinese People [corrected]. J Nutr. 2021;151(1):98-103. doi:10.1093/jn/nxaa332

37. Abdollahi A, Kamali Sarvestani H, Rafat Z, et al. The association between the level of serum 25(OH) vitamin D, obesity, and underlying diseases with the risk of developing COVID-19 infection: A case-control study of hospitalized patients in Tehran, Iran. J Med Virol. 2021;93(4):2359-2364. doi:10.1002/jmv.26726

38. Alguwaihes AM, Sabico S, Hasanato R, et al. Severe vitamin D deficiency is not related to SARS-CoV-2 infection but may increase mortality risk in hospitalized adults: a retrospective case-control study in an Arab Gulf country. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33(5):1415-1422. doi:10.1007/s40520-021-01831-0

39. Sulli A, Gotelli E, Casabella A, et al. Vitamin D and Lung Outcomes in Elderly COVID-19 Patients. Nutrients. 2021;13(3). doi:10.3390/nu13030717

40. Merzon E, Tworowski D, Gorohovski A, et al. Low plasma 25(OH) vitamin D level is associated with increased risk of COVID-19 infection: an Israeli population-based study. FEBS J. 2020;287(17):3693-3702. doi:10.1111/febs.15495

41. Faniyi AA, Lugg ST, Faustini SE, et al. Vitamin D status and seroconversion for COVID-19 in UK healthcare workers who isolated for COVID-19 like symptoms during the 2020 pandemic. bioRxiv. Published online October 6, 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.10.05.20206706

42. Livingston M, Plant A, Dunmore S, et al. Detectable respiratory SARS-CoV-2 RNA is associated with low vitamin D levels and high social deprivation. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(7):e14166. doi:10.1111/ijcp.14166

43. De Smet D, De Smet K, Herroelen P, Gryspeerdt S, Martens GA. Vitamin D deficiency as risk factor for severe COVID-19: a convergence of two pandemics. bioRxiv. Published online May 5, 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.05.01.20079376

44. Baktash V, Hosack T, Patel N, et al. Vitamin D status and outcomes for hospitalised older patients with COVID-19. Postgrad Med J. 2021;97(1149):442-447. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-138712

45. Mardani R, Alamdary A, Mousavi Nasab SD, Gholami R, Ahmadi N, Gholami A. Association of vitamin D with the modulation of the disease severity in COVID-19. Virus Res. 2020;289:198148. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198148

46. Fasano A, Cereda E, Barichella M, et al. COVID-19 in Parkinson’s Disease Patients Living in Lombardy, Italy. Mov Disord. 2020;35(7):1089-1093. doi:10.1002/mds.28176

47. Al-Daghri NM, Amer OE, Alotaibi NH, et al. Vitamin D status of Arab Gulf residents screened for SARS-CoV-2 and its association with COVID-19 infection: a multi-centre case-control study. J Transl Med. 2021;19(1):166. doi:10.1186/s12967-021-02838-x

48. Li X, van Geffen J, van Weele M, et al. Genetically-predicted vitamin D status, ambient UVB during the pandemic and COVID-19 risk in UK Biobank: Mendelian Randomisation study. bioRxiv. Published online August 22, 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.08.18.20177691

49. D’Avolio A, Avataneo V, Manca A, et al. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D Concentrations Are Lower in Patients with Positive PCR for SARS-CoV-2. Nutrients. 2020;12(5). doi:10.3390/nu12051359

50. Carpagnano GE, Di Lecce V, Quaranta VN, et al. Vitamin D deficiency as a predictor of poor prognosis in patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19. J Endocrinol Invest. 2021;44(4):765-771. doi:10.1007/s40618-020-01370-x

51. Abrishami A, Dalili N, Mohammadi Torbati P, et al. Possible association of vitamin D status with lung involvement and outcome in patients with COVID-19: a retrospective study. Eur J Nutr. 2021;60(4):2249-2257. doi:10.1007/s00394-020-02411-0

52. Maghbooli Z, Sahraian MA, Ebrahimi M, et al. Vitamin D sufficiency, a serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D at least 30 ng/mL reduced risk for adverse clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19 infection. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0239799. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0239799

53. Karonova TL, Andreeva АТ, Vashukova МА. serum 25(oH)D level in patients with CoVID-19. J Infectology. 2020;12(3):21-27. doi:10.22625/2072-6732-2020-12-3-21-27

54. Panagiotou G, Tee SA, Ihsan Y, et al. Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) levels in patients hospitalised with COVID-19 are associated with greater disease severity: results of a local audit of practice. bioRxiv. Published online June 23, 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.06.21.20136903

55. Karahan S, Katkat F. Impact of Serum 25(OH) Vitamin D Level on Mortality in Patients with COVID-19 in Turkey. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(2):189-196. doi:10.1007/s12603-020-1479-0

56. Jain A, Chaurasia R, Sengar NS, Singh M, Mahor S, Narain S. Analysis of vitamin D level among asymptomatic and critically ill COVID-19 patients and its correlation with inflammatory markers. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):20191. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-77093-z

57. Macaya F. Interaction between age and vitamin D deficiency in severe COVID-19 infection. Nutr Hosp. Published online 2020. Accessed August 31, 2021. https://www.nutricionhospitalaria.org/articles/03193/show

58. Kerget B, Kerget F, Kızıltunç A, et al. Evaluation of the relationship of serum vitamin D levels in COVID-19 patients with clinical course and prognosis. Tuberk Toraks. 2020;68(3):227-235. doi:10.5578/tt.70027

59. Faul JL, Kerley CP, Love B, et al. Vitamin D Deficiency and ARDS after SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Ir Med J. 2020;113(5):84. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32603575

60. Mendy A, Apewokin S, Wells AA, Morrow AL. Factors Associated with Hospitalization and Disease Severity in a Racially and Ethnically Diverse Population of COVID-19 Patients. medRxiv. Published online June 27, 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.06.25.20137323

61. Lau FH, Majumder R, Torabi R, et al. Vitamin D insufficiency is prevalent in severe COVID-19. bioRxiv. Published online April 28, 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.04.24.20075838

62. Radujkovic A, Hippchen T, Tiwari-Heckler S, Dreher S, Boxberger M, Merle U. Vitamin D Deficiency and Outcome of COVID-19 Patients. Nutrients. 2020;12(9). doi:10.3390/nu12092757

63. Pugach IZ, Pugach S. Strong correlation between prevalence of severe vitamin D deficiency and population mortality rate from COVID-19 in Europe. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2021;133(7-8):403-405. doi:10.1007/s00508-021-01833-y

64. Ali N. Role of vitamin D in preventing of COVID-19 infection, progression and severity. J Infect Public Health. 2020;13(10):1373-1380. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2020.06.021

65. Liu D, Tian Q, Zhang J, et al. Association of 25 hydroxyvitamin D concentration with risk of COVID-19: a Mendelian randomization study. bioRxiv. Published online August 13, 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.08.09.20171280

66. Chodick G, Nutman A, Yiekutiel N, Shalev V. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers are not associated with increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Travel Med. 2020;27(5). doi:10.1093/jtm/taaa069

67. Darling AL, Ahmadi KR, Ward KA, et al. Vitamin D concentration, body mass index, ethnicity and SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19: initial analysis of the first- reported UK Biobank Cohort positive cases (n 1474) compared with negative controls (n 4643). Proc Nutr Soc. 2021;80(OCE1). doi:10.1017/S0029665121000185

68. Vassiliou AG, Jahaj E, Pratikaki M, et al. Vitamin D deficiency correlates with a reduced number of natural killer cells in intensive care unit (ICU) and non-ICU patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Hellenic J Cardiol. Published online December 9, 2020. doi:10.1016/j.hjc.2020.11.011

69. Szeto B, Zucker JE, LaSota ED, et al. Vitamin D Status and COVID-19 Clinical Outcomes in Hospitalized Patients. Endocr Res. 2021;46(2):66-73. doi:10.1080/07435800.2020.1867162

70. Hastie CE, Mackay DF, Ho F, et al. Vitamin D concentrations and COVID-19 infection in UK Biobank. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(4):561-565. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050

71. Raisi-Estabragh Z, McCracken C, Bethell MS, et al. Greater risk of severe COVID-19 in Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic populations is not explained by cardiometabolic, socioeconomic or behavioural factors, or by 25(OH)-vitamin D status: study of 1326 cases from the UK Biobank. J Public Health . 2020;42(3):451-460. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdaa095

72. Pizzini A, Aichner M, Sahanic S, et al. Impact of Vitamin D Deficiency on COVID-19-A Prospective Analysis from the CovILD Registry. Nutrients. 2020;12(9). doi:10.3390/nu12092775

73. Cereda E, Bogliolo L, Klersy C, et al. Vitamin D 25OH deficiency in COVID-19 patients admitted to a tertiary referral hospital. Clin Nutr. 2021;40(4):2469-2472. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2020.10.055

74. Kaufman HW, Niles JK, Kroll MH, Bi C, Holick MF. SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates associated with circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0239252. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0239252

75. Campi I, Gennari L, Merlotti D, et al. Vitamin D and COVID-19 severity and related mortality: a prospective study in Italy. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):566. doi:10.1186/s12879-021-06281-7

76. Gaudio A, Murabito AR, Agodi A, Montineri A, Castellino P, D O CoV Research. Vitamin D Levels Are Reduced at the Time of Hospital Admission in Sicilian SARS-CoV-2-Positive Patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7). doi:10.3390/ijerph18073491

77. Demir M, Demir F, Aygun H. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with COVID-19 positivity and severity of the disease. J Med Virol. 2021;93(5):2992-2999. doi:10.1002/jmv.26832

78. Matin S, Fouladi N, Pahlevan Y, et al. The sufficient vitamin D and albumin level have a protective effect on COVID-19 infection. Arch Microbiol. Published online July 30, 2021. doi:10.1007/s00203-021-02482-5

79. Katz J, Yue S, Xue W. Increased risk for COVID-19 in patients with vitamin D deficiency. Nutrition. 2021;84:111106. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2020.111106

80. Israel A, Cicurel A, Feldhamer I, et al. The link between vitamin D deficiency and Covid-19 in a large population. bioRxiv. Published online September 7, 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.09.04.20188268

81. Elham AS, Azam K, Azam J, Mostafa L, Nasrin B, Marzieh N. Serum vitamin D, calcium, and zinc levels in patients with COVID-19. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2021;43:276-282. doi:10.1016/j.clnesp.2021.03.040

82. Oristrell J, Oliva JC, Casado E, et al. Vitamin D supplementation and COVID-19 risk: a population-based, cohort study. J Endocrinol Invest. Published online July 17, 2021. doi:10.1007/s40618-021-01639-9

83. Li S, Cao Z, Yang H, Zhang Y, Xu F, Wang Y. Metabolic Healthy Obesity, Vitamin D Status, and Risk of COVID-19. Aging Dis. 2021;12(1):61-71. doi:10.14336/AD.2020.1108

84. Cozier YC, Castro-Webb N, Hochberg NS, Rosenberg L, Albert MA, Palmer JR. Lower serum 25(OH)D levels associated with higher risk of COVID-19 infection in U.S. Black women. PLoS One. 2021;16(7):e0255132. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0255132

85. Tehrani S, Khabiri N, Moradi H, Mosavat MS, Khabiri SS. Evaluation of vitamin D levels in COVID-19 patients referred to Labafinejad hospital in Tehran and its relationship with disease severity and mortality. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2021;42:313-317. doi:10.1016/j.clnesp.2021.01.014

86. Angelidi AM, Belanger MJ, Lorinsky MK, et al. Vitamin D Status Is Associated With In-Hospital Mortality and Mechanical Ventilation: A Cohort of COVID-19 Hospitalized Patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(4):875-886. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.01.001

87. Infante M, Buoso A, Pieri M, et al. Low Vitamin D Status at Admission as a Risk Factor for Poor Survival in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19: An Italian Retrospective Study. J Am Coll Nutr. Published online February 18, 2021:1-16. doi:10.1080/07315724.2021.1877580

88. Bychinin MV, Klypa TV, Mandel IA, et al. Low Circulating Vitamin D in Intensive Care Unit-Admitted COVID-19 Patients as a Predictor of Negative Outcomes. J Nutr. 2021;151(8):2199-2205. doi:10.1093/jn/nxab107

89. Ling SF, Broad E, Murphy R, et al. High-Dose Cholecalciferol Booster Therapy is Associated with a Reduced Risk of Mortality in Patients with COVID-19: A Cross-Sectional Multi-Centre Observational Study. Nutrients. 2020;12(12). doi:10.3390/nu12123799

90. Alcala-Diaz JF, Limia-Perez L, Gomez-Huelgas R, et al. Calcifediol Treatment and Hospital Mortality Due to COVID-19: A Cohort Study. Nutrients. 2021;13(6). doi:10.3390/nu13061760

91. Bennouar S, Cherif AB, Kessira A, Bennouar D-E, Abdi S. Vitamin D Deficiency and Low Serum Calcium as Predictors of Poor Prognosis in Patients with Severe COVID-19. J Am Coll Nutr. 2021;40(2):104-110. doi:10.1080/07315724.2020.1856013

92. Vanegas-Cedillo PE, Bello-Chavolla OY, Ramírez-Pedraza N, et al. Serum Vitamin D levels are associated with increased COVID-19 severity and mortality independent of visceral adiposity. bioRxiv. Published online March 13, 2021. doi:10.1101/2021.03.12.21253490

93. Annweiler C, Beaudenon M, Simon R, et al. Vitamin D supplementation prior to or during COVID-19 associated with better 3-month survival in geriatric patients: Extension phase of the GERIA-COVID study. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2021;213:105958. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2021.105958

94. Adami G, Giollo A, Fassio A, et al. Vitamin D and disease severity in coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19). Reumatismo. 2021;72(4):189-196. doi:10.4081/reumatismo.2020.1333

95. Teama MAEM, Abdelhakam DA, Elmohamadi MA, Badr FM. Vitamin D deficiency as a predictor of severity in patients with COVID-19 infection. Sci Prog. 2021;104(3):368504211036854. doi:10.1177/00368504211036854

96. Diaz-Curiel M, Cabello A, Arboiro-Pinel R, et al. The relationship between 25(OH) vitamin D levels and COVID-19 onset and disease course in Spanish patients. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2021;212:105928. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2021.105928

97. Barassi A, Pezzilli R, Mondoni M, et al. Vitamin D in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) patients with non-invasive ventilation support. Panminerva Med. Published online January 25, 2021. doi:10.23736/S0031-0808.21.04277-4

98. Freitas AT, Calhau C, Antunes G, et al. Vitamin D-related polymorphisms and vitamin D levels as risk biomarkers of COVID-19 infection severity. bioRxiv. Published online March 26, 2021. doi:10.1101/2021.03.22.21254032

99. Sunnetcioglu A, Sunnetcioglu M, Gurbuz E, Bedirhanoglu S, Erginoguz A, Celik S. Serum 25(OH)D Deficiency and High D-Dimer Levels are Associated with COVID-19 Pneumonia. Clin Lab. 2021;67(7). doi:10.7754/Clin.Lab.2020.201050

100. Jude EB, Ling SF, Allcock R, Yeap BXY, Pappachan JM. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with higher hospitalisation risk from COVID-19: a retrospective case-control study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Published online June 17, 2021. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgab439

101. AlSafar H, Grant WB, Hijazi R, et al. COVID-19 Disease Severity and Death in Relation to Vitamin D Status among SARS-CoV-2-Positive UAE Residents. Nutrients. 2021;13(5). doi:10.3390/nu13051714

102. Charoenngam N, Shirvani A, Reddy N, Vodopivec DM, Apovian CM, Holick MF. Association of Vitamin D Status With Hospital Morbidity and Mortality in Adult Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19. Endocr Pract. 2021;27(4):271-278. doi:10.1016/j.eprac.2021.02.013

103. Mazziotti G, Lavezzi E, Brunetti A, et al. Vitamin D deficiency, secondary hyperparathyroidism and respiratory insufficiency in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Endocrinol Invest. Published online March 5, 2021. doi:10.1007/s40618-021-01535-2

104. Giannini S, Passeri G, Tripepi G, et al. Effectiveness of In-Hospital Cholecalciferol Use on Clinical Outcomes in Comorbid COVID-19 Patients: A Hypothesis-Generating Study. Nutrients. 2021;13(1). doi:10.3390/nu13010219

105. Basaran N, Adas M, Gokden Y, Turgut N, Yildirmak T, Guntas G. The relationship between vitamin D and the severity of COVID-19. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2021;122(3):200-205. doi:10.4149/BLL_2021_034

106. Orchard L, Baldry M, Nasim-Mohi M, et al. Vitamin-D levels and intensive care unit outcomes of a cohort of critically ill COVID-19 patients. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2021;59(6):1155-1163. doi:10.1515/cclm-2020-1567

107. Gavioli EM, Miyashita H, Hassaneen O, Siau E. An Evaluation of Serum 25-Hydroxy Vitamin D Levels in Patients with COVID-19 in New York City. J Am Coll Nutr. Published online February 19, 2021:1-6. doi:10.1080/07315724.2020.1869626

108. Herrera-Quintana L, Gamarra-Morales Y, Vázquez-Lorente H, et al. Bad Prognosis in Critical Ill Patients with COVID-19 during Short-Term ICU Stay regarding Vitamin D Levels. Nutrients. 2021;13(6). doi:10.3390/nu13061988

109. Sooriyaarachchi P, Jeyakumar DT, King N, Jayawardena R. Impact of vitamin D deficiency on COVID-19. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2021;44:372-378. doi:10.1016/j.clnesp.2021.05.011

110. Papadimitriou DT, Vassaras AK, Holick MF. Association between population vitamin D status and SARS-CoV-2 related serious-critical illness and deaths: An ecological integrative approach. World J Virol. 2021;10(3):111-129. doi:10.5501/wjv.v10.i3.111

111. Jayawardena R, Jeyakumar DT, Francis TV, Misra A. Impact of the vitamin D deficiency on COVID-19 infection and mortality in Asian countries. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021;15(3):757-764. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2021.03.006

112. Yadav D, Birdi A, Tomo S, Charan J, Bhardwaj P, Sharma P. Association of Vitamin D Status with COVID-19 Infection and Mortality in the Asia Pacific region: A Cross-Sectional Study. Indian J Clin Biochem. Published online February 3, 2021:1-6. doi:10.1007/s12291-020-00950-1

113. Mariani J, Giménez VMM, Bergam I, et al. Association Between Vitamin D Deficiency and COVID-19 Incidence, Complications, and Mortality in 46 Countries: An Ecological Study. Health Secur. 2021;19(3):302-308. doi:10.1089/hs.2020.0137

114. Ahmad A, Heumann C, Ali R, Oliver T. Mean Vitamin D levels in 19 European Countries & COVID-19 Mortality over 10 months. bioRxiv. Published online March 12, 2021. doi:10.1101/2021.03.11.21253361

115. Bakaloudi DR, Chourdakis M. Prevalence of vitamin D is not associated with the COVID-19 epidemic in Europe. A critical update of the existing evidence. medRxiv. Published online 2021. doi:10.1101/2021.03.04.21252885

116. Güven M, Gültekin H. The effect of high-dose parenteral vitamin D3 on COVID-19-related inhospital mortality in critical COVID-19 patients during intensive care unit admission: an observational cohort study. Eur J Clin Nutr. Published online July 23, 2021. doi:10.1038/s41430-021-00984-5

117. Singh S, Nimavat N, Kumar Singh A, Ahmad S, Sinha N. Prevalence of Low Level of Vitamin D Among COVID-19 Patients and Associated Risk Factors in India – A Hospital-Based Study. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:2523-2531. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S309003

118. Davoudi A, Najafi N, Aarabi M, et al. Lack of association between vitamin D insufficiency and clinical outcomes of patients with COVID-19 infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):450. doi:10.1186/s12879-021-06168-7

119. Brandão CMÁ, Chiamolera MI, Biscolla RPM, et al. No association between vitamin D status and COVID-19 infection in São Paulo, Brazil. Arch Endocrinol Metab. Published online March 19, 2021. doi:10.20945/2359-3997000000343

120. Jevalikar G, Mithal A, Singh A, et al. Lack of association of baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels with disease severity and mortality in Indian patients hospitalized for COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):6258. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-85809-y

121. Ferrari D, Locatelli M. No significant association between vitamin D and COVID-19: A retrospective study from a northern Italian hospital. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2021;91(3-4):200-203. doi:10.1024/0300-9831/a000687

122. Gupta D, Menon S, Criqui MH, Sun BK. Temporal association of reduced serum vitamin D with COVID-19 infection: A single-institution case-control and historical cohort study. medRxiv. Published online 2021. doi:10.1101/2021.06.03.21258330

123. Walk J, Dofferhoff ASM, van den Ouweland JMW, van Daal H, Janssen R. Vitamin D – contrary to vitamin K – does not associate with clinical outcome in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. bioRxiv. Published online November 9, 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.11.07.20227512

124. Al-Jarallah M, Rajan R, Dashti R, et al. In-hospital mortality in SARS-CoV-2 stratified by serum 25-hydroxy-vitamin D levels: A retrospective study. J Med Virol. 2021;93(10):5880-5885. doi:10.1002/jmv.27133

125. Lagadinou M, Zorbas B, Velissaris D. Vitamin D plasma levels in patients with COVID-19: a case series. Infez Med. 2021;29(2):224-228. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34061787

126. Reis BZ, Fernandes AL, Sales LP, et al. Influence of vitamin D status on hospital length of stay and prognosis in hospitalized patients with moderate to severe COVID-19: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;114(2):598-604. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqab151

127. Li Y, Tong CH, Bare LA, Devlin JJ. Assessment of the Association of Vitamin D Level With SARS-CoV-2 Seropositivity Among Working-Age Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5):e2111634. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11634

128. Nasiri M, Khodadadi J, Molaei S. Does vitamin D serum level affect prognosis of COVID-19 patients? Int J Infect Dis. 2021;107:264-267. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.04.083

129. Notz Q, Herrmann J, Schlesinger T, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in critically ill COVID-19 ARDS patients. Clin Nutr. Published online March 7, 2021. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2021.03.001

130. Entrenas Castillo M, Entrenas Costa LM, Vaquero Barrios JM, et al. “Effect of calcifediol treatment and best available therapy versus best available therapy on intensive care unit admission and mortality among patients hospitalized for COVID-19: A pilot randomized clinical study.” J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2020;203:105751. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2020.105751

131. Murai IH, Fernandes AL, Sales LP, et al. Effect of a Single High Dose of Vitamin D3 on Hospital Length of Stay in Patients With Moderate to Severe COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021;325(11):1053-1060. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.26848

132. Rastogi A, Bhansali A, Khare N, et al. Short term, high-dose vitamin D supplementation for COVID-19 disease: a randomised, placebo-controlled, study (SHADE study). Postgrad Med J. Published online November 12, 2020. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-139065

133. Sánchez-Zuno GA, González-Estevez G, Matuz-Flores MG, et al. Vitamin D Levels in COVID-19 Outpatients from Western Mexico: Clinical Correlation and Effect of Its Supplementation. J Clin Med Res. 2021;10(11). doi:10.3390/jcm10112378

134. Sabico S, Enani MA, Sheshah E, et al. Effects of a 2-Week 5000 IU versus 1000 IU Vitamin D3 Supplementation on Recovery of Symptoms in Patients with Mild to Moderate Covid-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutrients. 2021;13(7). doi:10.3390/nu13072170

135. Lakkireddy M, Gadiga SG, Malathi RD, et al. Impact of daily high dose oral vitamin D therapy on the inflammatory markers in patients with COVID 19 disease. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):10641. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-90189-4

136. Ghasemian R, Shamshirian A, Heydari K, et al. The role of vitamin D in the age of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pract. Published online July 29, 2021:e14675. doi:10.1111/ijcp.14675

137. Crafa A, Cannarella R, Condorelli RA, et al. Influence of 25-hydroxy-cholecalciferol levels on SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 severity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;37:100967. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100967

138. Bassatne A, Basbous M, Chakhtoura M, El Zein O, Rahme M, El-Hajj Fuleihan G. The link between COVID-19 and VItamin D (VIVID): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Metabolism. 2021;119:154753. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2021.154753

139. Shah K, P V V, Pandya A, Saxena D. Low vitamin D levels and prognosis in a COVID-19 paediatric population: a systematic review. QJM. Published online July 22, 2021. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcab202

140. Lou Y-R, Molnár F, Peräkylä M, et al. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D(3) is an agonistic vitamin D receptor ligand. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;118(3):162-170. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.11.011

141. Susa T, Iizuka M, Okinaga H, Tamamori-Adachi M, Okazaki T. Without 1α-hydroxylation, the gene expression profile of 25(OH)D3 treatment overlaps deeply with that of 1,25(OH)2D3 in prostate cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):9024. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-27441-x

142. Waldron JL, Ashby HL, Cornes MP, et al. Vitamin D: a negative acute phase reactant. J Clin Pathol. 2013;66(7):620-622. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2012-201301

143. Stroehlein JK, Wallqvist J, Iannizzi C, et al. Vitamin D supplementation for the treatment of COVID-19: a living systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;5:CD015043. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD015043

144. Jetter A, Egli A, Dawson-Hughes B, et al. Pharmacokinetics of oral vitamin D(3) and calcifediol. Bone. 2014;59:14-19. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24516879

145. Ilahi M, Armas LAG, Heaney RP. Pharmacokinetics of a single, large dose of cholecalciferol. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(3):688-691. doi:10.1093/ajcn/87.3.688

146. Jolliffe DA, Stefanidis C, Wang Z, et al. Vitamin D Metabolism Is Dysregulated in Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(3):371-382. doi:10.1164/rccm.201909-1867OC

147. Bouillon R, Bikle D. Vitamin D Metabolism Revised: Fall of Dogmas. J Bone Miner Res. 2019;34(11):1985-1992. doi:10.1002/jbmr.3884

148. Jungreis I, Kellis M. Mathematical analysis of Córdoba calcifediol trial suggests strong role for Vitamin D in reducing ICU admissions of hospitalized COVID-19 patients. medRxiv. Published online November 12, 2020:2020.11.08.20222638. doi:10.1101/2020.11.08.20222638

149. Nogues X, Ovejero D, Pineda-Moncusí M, et al. Calcifediol treatment and COVID-19-related outcomes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. Published online June 7, 2021. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgab405

150. Spiesman IG. MASSIVE DOSES OF VITAMINS A AND D IN THE PREVENTION OF THE COMMON COLD. Arch Otolaryngol. 1941;34(4):787-791. doi:10.1001/archotol.1941.00660040843010

151. Green HN, Mellanby E. VITAMIN A AS AN ANTI-INFECTIVE AGENT. Br Med J. 1928;2(3537):691-696. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.3537.691

152. Semba RD. Vitamin A as “anti-infective” therapy, 1920-1940. J Nutr. 1999;129(4):783-791. doi:10.1093/jn/129.4.783

153. Berkner KL, Runge KW. The physiology of vitamin K nutriture and vitamin K-dependent protein function in atherosclerosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2(12):2118-2132. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00968.x

154. Farzaneh-Far A, Weissberg PL, Proudfoot D, Shanahan CM. Transcriptional regulation of matrix gla protein. Z Kardiol. 2001;90 Suppl 3:38-42. doi:10.1007/s003920170040

155. Kirfel J, Kelter M, Cancela LM, Price PA, Schüle R. Identification of a novel negative retinoic acid responsive element in the promoter of the human matrix Gla protein gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(6):2227-2232. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.6.2227

156. Sarohan AR, Akelma H, Araç E, Aslan Ö. Retinol Depletion in Severe COVID-19. bioRxiv. Published online February 1, 2021. doi:10.1101/2021.01.30.21250844

157. Dofferhoff ASM, Piscaer I, Schurgers LJ, et al. Reduced vitamin K status as a potentially modifiable risk factor of severe COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. Published online August 27, 2020. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1258

158. Wang K, Chen S, Xie W, Wan Y-JY. Retinoids induce cytochrome P450 3A4 through RXR/VDR-mediated pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75(11):2204-2213. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2008.02.030

159. Tabb MM, Sun A, Zhou C, et al. Vitamin K2 regulation of bone homeostasis is mediated by the steroid and xenobiotic receptor SXR. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(45):43919-43927. doi:10.1074/jbc.M303136200