Adventures in Zone 2 Cardio Training | Part 1

This may be the main missing ingredient in my training!

Zone 2 cardio training has been blurrily on my radar from hearing Peter Attia talk about it a lot as being essential to longevity.

A little over a month ago, I listened to his two interviews with Iñigo San Millán, an exercise physiologist responsible for much of the primary research on zone 2. This rapidly made me realize that zone 2 may be the primary missing ingredient in my training.

Here are the two interviews:

#85 – Iñigo San Millán, Ph.D.: Mitochondria, exercise, and metabolic health

201 - Deep dive back into Zone 2 Training | Iñigo San-Millán, Ph.D. & Peter Attia, M.D.

I also listened to this interview with him on the show Upside Strength:

What Is Zone 2?

To briefly summarize the key points I learned about what zone 2 is:

Zone 2 is the point at which your mitochondria first shift toward anaerobic glycolysis, because fat oxidation can no longer handle the intensity of your workout. This is not primarily glycolytic exercise. It is primarily fat-burning. However, at this point the demand to burn fat is being taxed so much that producing lactate during glycolysis must help out. It is not high intensity at all. It is moderate intensity, and you should be able to sustain the pace for an hour.

Zone 2, in my estimation, is the epitome of the much-maligned “steady state cardio.” I picture the standard aerobic trainer of the 80s, thought to be completely wrong-headed in the world of CrossFit and Paleo.

The best way to know you are in Zone 2 is with a lactate meter. Short of that, the best way is not your heart rate, as written everywhere on the internet, but is rather your rate of perceived exertion. You know that you are in zone 2 if you could sustain the exercise for an hour and talk the entire time, but talking would make you slightly and annoyingly out of breath. If you were on a phone conversation with someone, they would know you were exercising by how you were breathing while talking to them.

Elite runner and exercise scientist Mads Taersboel gave me some help in understanding this. If I understand correctly, you could plot your blood lactate at increasing intensity and you would find several inflection points demarcating the different zones of exercise. The zone between the first and second inflection points is zone 2.

Using heart rate has severe limitations. First, if you haven’t determined your maximal heart rate empirically by seeing how high it can get when you push yourself to absolute maximum, calculating your max heart rate from your age is both inaccurate and imprecise. Second, the percentage of your max heart rate corresponding to zone 2 is broad; it may overlap with zone 2 but it can’t precisely demarcate the beginning and end of it. Third, in talking with a friend who owns a gym and trains people in zone 2, when people are poorly trained in zone 2 their heart rate is nowhere near as high as the calculations predict; as they become more trained, their heart rate becomes in line with the predictions. Someone very well trained could reach a heart rate in zone 2 that is higher than the calculations suggest.

When you train in zone 2, you are doing two things: your slow-twitch fibers are trained to increase mitochondrial density and sustain long periods with very high fat oxidation; since your fast-twitch fibers are generating a slow and steady trickle of lactate, you are training your slow-twitch fibers to consume the lactate and become lactate disposal sinks.

Why Care About Zone 2?

So, why is this important?

San Millán argues that zone 2 is the most critical exercise for metabolic health. He judges metabolic health by how dependent your mitochondria are on anaerobic glycolysis. He says there are two types of people who display poor metabolic health by this definition: diabetics, and people who only do bodybuilding and high-intensity interval training.

Whoa. I felt like that was a direct stab at me.

I’ve been thinking of my activity in three categories: light activity, weight lifting, and high-intensity interval training. My light activity is generally walking around 2 miles per hour. I get a lot of that, but it doesn’t reach zone 2. It is zone 1.

For most of my life I have not been very tolerant of fasting. I have a strong hypothesis for why that I will cover in a separate post, but I do think part of it is my lack of zone 2. Zone 2 is not the point of maximal fat oxidation, but it is the maximal intensity of fat oxidation that can be sustained for long periods. I suspect that zone 2 cardio is important to improving fasting tolerance.

In line with this emphasis on fat oxidation, my trainer friend says he has seen zone 2 training take off that last bit of fat that seems so stubborn in many people.

Since zone 2 fitness is in some respects the opposite of diabetes — that is, you can exercise for long periods at high intensity without needing to generate lactate — Attia sees its metabolic benefits as central to his longevity framework.

San Millán hypothesizes it could play a role in preventing cancer. Moderate intensity exercise is associated with improved cancer outcomes. San Millán believes this may be because cancer cells use lactate as a regulatory signal that improves their survival, while zone 2 training is optimized to promote lactate clearance.

Of course, this research comes out of exercise science, and this is because zone 2 training is essential to athletic training. It is not just essential to endurance athletes. It builds the aerobic base that supports higher intensity training.

Why did Rocky train for boxing with moderate running?

He was building his aerobic base.

My gym-owning friend told me recently that since he has been doing large volumes of zone 2, his CrossFit-style high intensity workouts have gotten much better even though he doesn’t train them often. I believe this is because these workouts generate a lot of lactate, and lactate, if not cleared, will slow down energy metabolism in muscle to prevent excessive acidity. If you don’t do zone 2, you have to export the lactate to your liver to be turned back into glucose in the Cori Cycle. If you do zone 2, the lactate is much more quickly consumed by the slow-twitch fibers. Thus, lots of zone 2 builds a base of lactate clearance that allows high-intensity to be sustained much more effectively.

San Millán says that elite athletes, even if their sport is short bursts of high intensity, spend 80% of their training time in zone 2.

Can Zone 2 Improve Postural Endurance?

I have a sneaking suspicion that doing zone 2 will improve my postural endurance.

In the past, the most helpful advice I ever got for my neck and head tension was to use a rowing machine. I did 45 minutes a session several times a week during grad school, and it was enormously effective.

When I would tell people this in my nutrition circles, I would get funny looks and people asking me why I would do anything for 45 minutes instead of doing short bouts of high intensity, and asking me why I didn’t just do kettlebell rows.

I stopped doing this because I just didn’t have the time.

Later, I came across a theory that muscle mass imbalance could explain it. By using a rowing machine, I was building muscles in my shoulders and back. So I started focusing on hypertrophy exercises. I ultimately found these quite useless.

In the last couple of years, I found that 30 minutes on an eliptical 3-5 times a week was the most time-effective thing I could do for my neck and head tension. 3 times a week would help preserve my gains, 4-5 times a week was needed for progress. I thought this was by reducing neural overstimulation. I talked to a doctor who thought it was by improving circulation of joint fluid.

Over the last year I have been seeing a physical therapist and making remarkable progress. My physical therapy exercises were much more specifically geared to my spinal mobility than the eliptical was, and they took time, so I sold my eliptical.

A few months in, my physio told me that she had never seen anyone with such poor endurance sitting on a medicine ball as me. She said it seemed like I was relying entirely on my fast-twitch muscle fibers and had no slow-twitch activity.

Is it possible that I had no slow-twitch support because I wasn’t training my slow-twitch fibers enough?

Looking back, I do wonder whether the two examples of purposeful zone 2 training I have had in the past were the rowing machine and the eliptical, both of which were the most time-efficient things I had ever done to improve my symptoms, and both of which needed to be done at about four hours a week to achieve results.

So, one of my primary metrics for my zone 2 work will be to see if it can improve my postural endurance and the head and neck tension I have.

My Experiments in Zone 2: Overview

San Millán says that zone 2 should be one-hour bouts and should be done at least 2-3 times a week for maintenance, but must be done 4-5 times a week to make real gains in metabolic health.

My initial experience contradicts this. I have had remarkable progress doing zone 2 for five one-hour sessions across one month. This is a rate just barely higher than once a week.

However, this may simply be because I am so poorly trained in zone 2 that I have nowhere to go but up.

Still, it may also be that I adapt very well to zone 2 for genetic reasons or that my diet, supplements, and lifestyle are very supportive of progress.

Or, it may simply be the power of taking such precise measurements, discussed toward the end.

I look forward to continuing these experiments to see if I can sustain this rate of progress or to see whether progressing gets harder and harder as I get more trained.

Although I suspect rowing would be superior for my upper body postural endurance since I would be ensuring that my shoulder and back muscles are heavily involved in the zone 2 intensity, for efficiency’s sake I started with my office treadmill, which goes up to a maximum speed of 4.0 miles per hour. I figured the systemic zone 2 would help my whole body, and I wanted to maximize my time working on my book without having to go to a gym to workout.

However, after just five sessions, I made such rapid progress that I maxed out my ability to get a zone 2 workout in on my office treadmill!

My Experiments in Zone 2: Details

At first I tried using my heart rate, but I found it wildly inaccurate. My heart rate calculations say zone 2 is 133-145 beats per minute, but I found there was no way on earth I could sustain this heart rate for an hour.

Since the rate of perceived exertion seems to subjective to me, and since I work out alone, I thought it best to invest in a lactate meter.

Using Attia’s suggestion, I bought a Nova Biomedical Lactate plus. It was extremely frustrating that the strips are so expensive yet the learning curve is such that I wasted numerous strips before I got the practice down.

A couple of my lessons:

Dump the strips out of the bottle onto a clean tissue first, and take out all the strips you need for the workout, touching them only in the middle. Cover them with another clean tissue. Touching the remaining ones only in the middle, put them back in the bottle.

This meter is more sensitive to having enough volume than glucose or ketone meters are. It is also extremely sensitive to taking the blood up quickly. Make sure you have a very good-sized droplet before attempting to test it. If the blood is taken in too slowly or not enough is taken in, the meter will tell you it is calculating and then give you an error. I wasted 3-4 of these luxuriously priced strips before I learned the art of getting a big blood droplet and drawing it quickly.

Attia keeps a bucket of soapy water and clean water with him so he can wash his finger first to remove any lactate in sweat. Taersboel told me it should be sufficient to wipe the sweat off with a clean tissue, cleanse with an alcohol pad, then dry with a clean tissue, so I do this.

If you try any of this, be sure to follow any other kit instructions, such as wiping the initial drop of blood away before testing the second drop.

My first two experiments in August were duds.

The first was a dud because I couldn’t figure out why the meter gave me an error four times and I hadn’t yet discovered the big droplet quick uptake rule.

The second was a dud because 60 minutes at 3.0 miles per hour (mph) only raised my lactate from 0.8 to 0.9.

Attia likes to get near the border of 2.0 millimoles per liter (mM), but stay just under. Taersboel told me most beginners are better served by aiming for a 0.3-0.5 mM increase over their baseline, since staying near the beginning of their zone 2 will make it easier to sustain the pace for longer.

Over August, after these two duds, I finished version 8 of the COVID guide and the COVID vaccine side effect guide, which required working through 3 weekends, often working over 10 hours a day, and precluded any exercise at all. While this may sound unhealthily extreme, I needed to get these two tasks out of my head before returning to full-time work on the Vitamins and Minerals 101 book, and I am very happy I did that. I then went on a road trip and shut my brain off for a week to make up for those lost weekends.

Come September, my experiments were on.

On September 2, my baseline lactate was 0.7 mM. Fasting, but with 2 cups of coffee with cream and stevia, 4.0 mph on my office treadmill rose my lactate to 1.7. This seemed too high since it was double the top of the 0.3-0.5 mM increase rule. I dropped it to 3.5 mph, and my lactate fell to 0.9. This was too low. I increased it to 3.7 mph, and my lactate rose to 1.5.

This showed that 3.5 mph failed to reach zone 2, while 3.7-4.0 mph was somewhat aggressively in zone 2.

This is what it looks like over time:

However, if we plot lactate against speed (as a proxy for intensity) rather than over time, you can see there’s an obvious inflection point that occurs somewhere after 3.5 mph, but before 3.7 mph:

Three days later, on September 5, I did my second experiment. My goal was to see if 3.6 mph, which I hadn’t tried yet, was the true bottom of my zone 2.

Once again, my baseline lactate was 0.7 mM. Fasting, with one cup of coffee with stevia and cream behind me and the other during my workout, I aimed to find Taersboel’s sweet spot of 0.3-0.5 mM above baseline in the 3.6-3.7 mph range.

After 15 minutes of 3.6 mph, my lactate went up to 1.0 mM, which seemed good enough, but after another 15 minutes, it dropped back down to 0.8 mM. I believe this is because lactate consumption my by slow-twitch fibers rose to compensate for the initial increase, or because my liver kicked in to turn the lactate to glucose. So I went up to 3.7 mph, but this made my lactate shoot up to 1.7 mM. This was way beyond the top of Taersboel’s 0.3-0.5 mM above baseline range, so I went back to 3.6 mph and my lactate went down to 0.9 mM.

From this experiment, I could establish that 3.7 mph was the lowest speed at which I could truly get into zone 2.

There was no speed at which I could get a sustainable rise of 0.3-0.5 mM. Perhaps I could have done this at 3.65 mph, but my treadmill doesn’t have a setting for that.

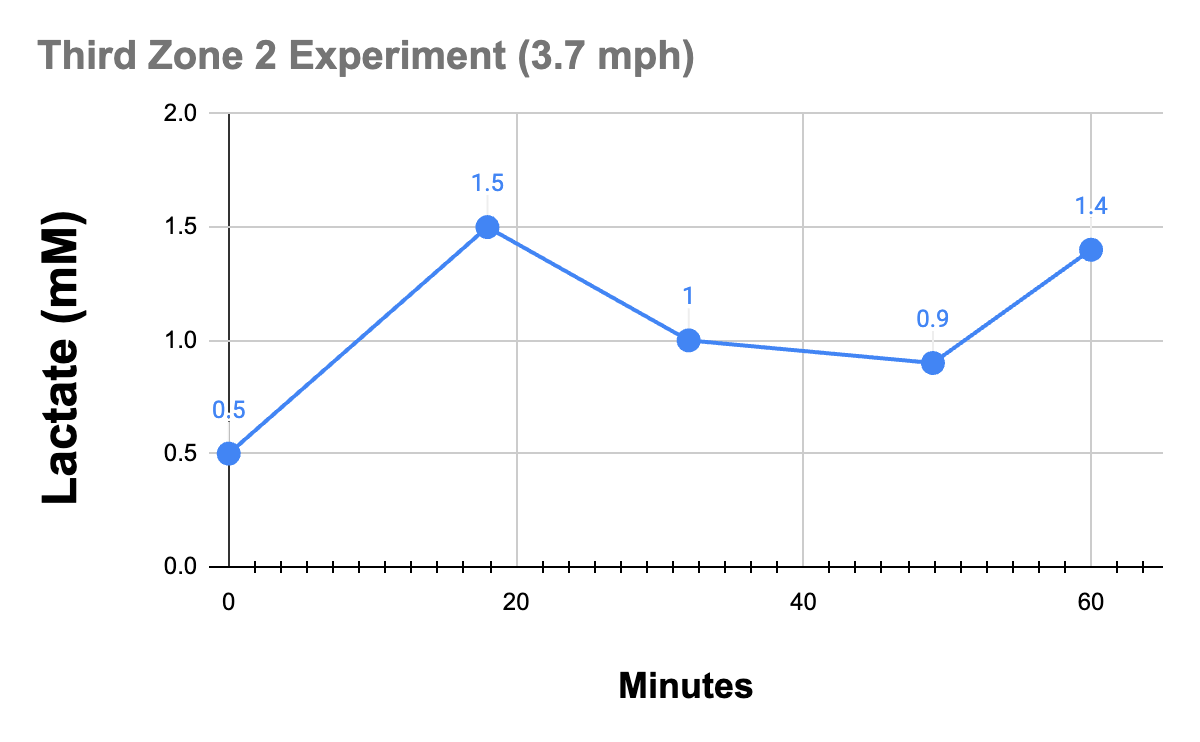

Having established 3.7 mph as the bottom of my zone 2, my third experiment was to stay at this pace for 60 minutes and see if my lactate stayed at zone 2 levels. I did this four days later, on September 9.

My baseline lactate was 0.5. That day, I had a lot of blood drawn in the morning (over 100 mL), and ate breakfast afterward. So this was my first day where I wasn’t fasting. I also did it later in the afternoon (a little after 2PM) rather than closer to 10AM. It was a success:

I don’t know what accounts for the dip in the middle. It might have been me fiddling around too much while getting the measurement, or maybe it represents something physiological, such as peak lactate consumption by slow-twitch fibers, or my liver turning it into glucose.

However, all four time points are above Taersboel’s 0.3-0.5 mM increase range, so this was a successful sustaining of zone 2 for an hour.

After only a single successful session staying in zone 2 for an hour, my threshold increased in the third experiment!

That weekend, I had an average of 1.5 drinks a day for three days. On Monday, September 12, I woke up early, and in my typical fasting-with-stevia-sweetened-coffee-and-cream fashion, started my zone 2 workout at just after 8 AM.

My baseline lactate was 0.9 mM.

I had lost 3.7 mph!

15 minutes of 3.7 mph only raised my lactate to 1.1 mM, below the minimal threshold. So I increased to 3.8 mph, but my lactate simply dropped to 0.9 mM, my baseline. Then I increased to 3.9 mph, and stayed there for the last half hour of my workout. From this measly 0.1 mph increase, my lactate shot up to 1.7 mM and then in the last 15 minutes dropped to 1.2 mM.

This experiment showed that my zone 2 threshold had increased to 3.9 mph. While my last measurement just makes it into the bottom of the zone 2 threshold, I doubt that it would have stayed in zone 2 the whole time if I had done 3.9 mph for an hour.

So that’s 30 minutes flirting with the edge of zone 2, and 30 minutes in it.

At this point it was evident that I would only have one or two more workouts before I outgrew the office treadmill.

My fifth experiment occurred after even more alcohol consumption, because I had a drink for a day for three days and then unexpectedly went to a social event I wasn’t planning on where I had 2.5 drinks. The next morning, on September 21, just before 10AM, I conducted the next experiment in typical fasting-with-coffee fashion.

My baseline lactate was 0.9 mM. 3.9 mph provoked a rise to 1.4 after 15 minutes, but that fell to 0.8 mM — beneath my baseline — at the 30-minute mark.

I increased to 4.0 mph. Again, I got a rise to 1.4 mM and then a fall to 1.0.

So that’s another 30 minutes flirting with the edge of zone 2 and 30 minutes in it, although this time the zone 2 was the first 15 minutes of each speed, rather than the last 30 minutes of the workout once I found a high enough speed.

At this point, I was reasonably sure I had outgrown my office treadmill. If 4.0 mph couldn’t keep me in zone 2 for 30 minutes, it probably couldn’t keep me there for 60.

Could I get another 15 minutes out of it?

Nope.

Eight days after the fifth experiment, this morning, I performed the sixth. No alcohol for more than a week, typical fasting-and-coffee regimen. I had gone to my physical therapy appointment first, so started late.

My lactate was 0.7 mM in the morning and was 0.9 mM by the time I did the workout.

Power walking at 4.0 mph didn’t raise my lactate at all. I tried switching to a jogging stance, to see if that would increase the intensity, but it just dropped my lactate slightly to 0.8 mM.

Alas, I had outgrown the office treadmill.

Across these experiments, I tracked my heart rate with a FitBit. My peak heart rate started out at 110 when I was in zone 2, and in subsequent workouts was 117-126. It seems like training led me to do more intensity at a greater heart rate while achieving zone 2, but this is still way under the 133-145 bpm suggested from the calculators you can find floating all over the internet. I expect the heart rate I attain while in zone 2 to keep increasing as I keep training.

Reflections on My Experiments

It seems like I spent as much time chasing zone 2 than in it. If we ignore the first two duds and start the clock at my first successful experiment on September 2, I spent 5.5 hours walking and 2 hours and 45 minutes of that — exactly half of it — was spent in zone 2.

However, I doubt that the zone 2 threshold is as binary as our name for it suggests. If I am just under the threshold, most likely my mitochondria have already started generating more lactate but it’s being quickly digested by my slow-twitch fibers or sufficiently turned into glucose by my liver, such that my slow-twitch fibers are still getting trained to consume lactate and are still engaging in very high fat oxidation.

So, it’s probably better to say I was “officially” in zone 2 for 2.5 hours, but I was effectively experiencing the physiological benefits of zone 2 for 5 hours, since I was otherwise so close to the threshold.

I would have spent more time in zone 2 if I had increased at 0.2 mph per workout rather than 0.1, but I also would have gotten very little use out of my treadmill!

I don’t know why I’m making so much progress so fast. It’s certainly the case that I am untrained and have nowhere to go but up, but I cannot rule in or out that other things I am doing with food, sunlight, grounding, supplements, stress management, and so on, aren’t contributing to the fast progress as well. The only way to know will be to keep training.

While the lactate measurements are expensive, I don’t see how I could have gotten anywhere near the precision using my rate of perceived exertion. Maybe I just don’t trust myself enough, but I don’t believe it.

Without the precision, I wouldn’t be able to train right at the edge of where I want to be, and I do not believe I would make progress so rapidly.

What gets measured gets managed (thanks, Drucker!) and I believe I am managing training at the optimal level by measuring it more precisely.

Where to Go From Here

From here, I will need to start rowing, which I think will also be ideal for my postural goals. I’d like to do more experiments correlating zone 2 with other metrics, such as oxygen consumption, respiratory quotient, and sticking with the heart rate correlations.

I do intend to use the lactate meter less, but I first want to establish the correlates I can use to replace it with precision.

I think more measurements sooner will allow me to take fewer measurements later while staying more tightly optimized the whole time.

I will also take the major lesson from these experiments and move forward faster. I’ll have to figure out how to translate mph on the office treadmill into metrics a rower will give me, and then try to stay ahead of zone 2 rather than endlessly chasing its tail.

Have you had any experience with zone 2? Let me know in the comments!

Join the Next Live Q&A

Have a question for me? Ask it at the next Q&A! Learn more here.

Join the Masterpass

Masterpass members get access to premium content (preview the premium posts here), all my ebook guides for free (see the collection of ebook guides here), monthly live Q&A sessions (see when the next session is here), all my courses for free (see the collection here), and exclusive access to massive discounts (see the specific discounts available by clicking here). Upgrade your subscription to include Masterpass membership with this button:

Learn more about the Masterpass here.

Please Show this Post Some Love

Please like and share this post on the Substack web site. This will help spread it far and wide, as subscriber likes drive the Substack algorithm. Likes from paid subscribers count the most, but likes from free subscribers come in the highest numbers and are the foundation for spreading the content.

Take a Look at the Store

At no extra cost to you, please consider buying products from one of my popular affiliates using these links: Paleovalley, Magic Spoon breakfast cereal, LMNT, Seeking Health, Ancestral Supplements, MASA chips. Find more affiliates here.

For $2.99, you can purchase The Vitamins and Minerals 101 Cliff Notes, a bullet point summary of all the most important things I’ve learned in over 15 years of studying nutrition science.

For $10, you can purchase The Food and Supplement Guide for the Coronavirus, my protocol for prevention and for what to do if you get sick.

For $10, you can purchase Healing From COVID Vaccine Side Effects for yourself or a loved one if dealing with this issue. It also contains an extensive well-referenced scientific review, so you can also use this just to learn more about my research into the COVID vaccines.

For $29.99, you can purchase a copy of my ebook, Testing Nutritional Status: The Ultimate Cheat Sheet, my complete system for managing your nutritional status using dietary analysis, a survey of just under 200 signs and symptoms, and a comprehensive guide to proper interpretation of labwork.

All I know is that hopping on the mini trampoline and long bike rides bring me more joy than any other form of exercise!

Thanks for this ...

I bought a gravel bike last year and I hit the trails 4 or 5x per week -- 60 to 90 minute rides... I'd estimate that 80% of the rides are on flat or moderate hills with the remainder being steep hills...

I'm just a bit breathless for the 80% -- but on the steep inclines I go as hard as I can.

Great results from this in terms of overall fitness - I play a lot of ice hockey in the winter and I found this base really helped... previously I was all about HIIT... that clearly was not working.

I also do partial Body Pump classes from Les Mills online. One day I'll do chest back and some abs... another day arms and abs... I can complete that in less than 15 minutes.. and it's great for strength