In 2022, inspired by Peter Attia’s interviews with Inigo San Millan, I experimented with measuring my lactate during exercise to calibrate my cardio to zone 2.

The gist of the argument in favor of this is that 80% of your cardio training should be in zone 2, because this maximizes the mitochondrial capacity of slow-twitch muscle fibers. This provides an aerobic base to support higher-intensity workouts, serves as a lactate sink to clear the lactate generated by fast-twitch fibers, and supports both maximal athletic performance and optimal glucose metabolism.

I quickly decided that measuring lactate during exercise — outside of a research study in an exercise science lab into your personal physiology or a formal research study of multiple subjects — is a distraction from the actual goal of the exercise with no real utility.

This is in complete contrast to my view on measuring lactate in the fasting state, one hour postprandially, or at specific times during the day that correlate with cyclical health problems. I think this has profound utility and should always be measured alongside blood glucose. I’ve explained this in great detail The Four Markers Every Expert Should, But Doesn’t, Analyze.

I have several problems with the idea of trying to micromanage zone 2 status with any kind of precision:

My understanding of the lactate threshold definition is that as your blood lactate reaches its first inflection point upwards, this reflects the point at which the slow-twitch fibers ability to act as a lactate sink has been maximized. The extra lactate spills over into the blood, and you now know your slow-twitch fibers are being trained maximally. Is there any reason to believe that if I train 10% under this point, I am not receiving 90% of the benefit? I do not see such a reason.

Measuring lactate is impossible during most real-world scenarios, especially if the exercise is done outside. Done inside, it still interrupts the rhythm of the exercise and takes attention away from performing the exercise.

A much more practical alternative to measuring lactate is the “talk test,” where zone 2 should reflect the ability to carry on a conversation but have difficulty with it, where someone on the phone could tell you were exercising because your breathing and talking are noticeably labored. I exercise alone almost always, and while I could see using this as an intermittent gauge, it is difficult to use it practically in any kind of continuous manner. I substituted for this maintaining a pace where I could still mostly breathe through my nose, but at which I was motivated to breath through my mouth to obtain more air, and at which I could hear myself breathing.

As shown in the Appendix below, the first increment on the talk test actually skips over lactate-based zone 2 measurements entirely. From among five different definitions of zone 2 there are NONE that can identify any other definition with anything remotely approximating single-zone precision. From among these, percent of maximal heart rate is clearly the best thing you can measure at home, yet not even it can identify zone 2 with any precision when defined by lactate, oxygen consumption, fat oxidation, or breathing rate. Therefore, all “precision” you try to obtain in identifying zone 2 is a fantasy.

So, I started calling my workouts “zone 2-style” simply as a nickname for a model of one type of cardio workout that met the following criteria:

I used an approximately sustained pace for one hour.

I felt like I could not have done much more than an hour while maintaining that pace.

I could hear myself breathing and wanted to breathe through my mouth but could keep breathing 90% through my nose.

I also noted another clue after my workout: I get intensely flushed in the face and it lasts long enough that I can shower and change and will still be flushed. I see this as confirmation that my “zone 2-style” workout generated the physiological response I was looking for.

I then reflected on another problem I had with the concept of running or cycling in zone 2: If I am trying to increase mitochondrial density in my muscles by being in zone 2, how on earth am I going to do so in anything other than my legs while running or cycling?

Maybe your heart is in zone 2.

Maybe your lungs are in zone 2.

But if you are running or cycling the only muscles in zone 2 are in your lower body. There is no way on earth your arms, trunk, and rotational muscles are in zone 2.

Now if you are a competitive runner, by all means run. If you are a competitive cyclist, by all means cycle. If these are your favorite hobbies, hobby away.

My point is simply that if you are engaging in this type of exercise specifically for its health value, it should be something that is conferring that health value on as much of your body as possible.

I therefore replaced running with two types of zone 2 workouts:

Rowing. I try to focus on my abs staying tight and my elbows being drawn all the way back because my shoulders are too forward and my ribs too flared in my default posture, so I see this as building the correct postural endurance. Rowing keeps my upper and lower body engaged to a similar degree, but does nothing for rotational forces.

Boxing. I box against a heavy bag with an uppercut attachment with a series of jabs, crosses, hooks, and uppercuts. I focus on my technical skill as much as I can without detracting from the pace and effort, while I focus more on technical skills in different boxing workouts. This covers horizontal and diagonal upward rotational force very well. To the extent of my current boxing knowledge, I believe that it is deficient in downward diagonal force transmission, with blocking being the main opportunity to engage that direction. So, someday when I have a house with a firepit and fireplace I will supplement this with chopping wood but I will have to train safely chopping it ambidextrously.

I am not entirely sure my abs are getting the same stimulus as my other muscles. For this reason, I make my weekly ab workout focus on steadily building endurance, and I also make it a point to train my abs for long periods by contracting them to stack my ribs properly while I am working or do other random things.

Finally, I have a huge problem with the concept that has been put forward that people should get three to four hours per week of zone 2 cardio.

While this may be the minimal effective dose to show metabolic benefits in short-term studies — and I will say that my fasting glucose is improved better by my “zone 2-style” workouts than by anything else — it is almost impossible for anyone, including me, to focus on this much zone 2 work without displacing other important workouts.

Instead, I assume that if I am consistently getting better at something, my frequency is just fine.

I find that I need to do my “zone 2-style” work at least once every two weeks to keep improving. I aim to get it in once a week, I force myself to get it in at least once every two weeks, and I wind up getting it in about once every ten days as a result.

I think it is crazy to allow cardio work to come at the expense of resistance training and mobility work, or to allow zone 2 workouts to come at the expense of higher-intensity workouts.

If you have enough workout time to at minimum do enough resistance exercise to be constantly getting stronger without ever losing any muscle mass (providing you are already in the upper half of muscularity for your age and sex; otherwise you need to immediately start gaining muscle); to be always improving your posture, joint alignment, and mobility; to be hitting high intensities; and to be getting 3-4 hours of “zone 2” training then by all means do it.

If you are like me, though, and cannot fit all of these things into one week, do an hour of so-called “zone 2” (ish) training at least once every two weeks, track your progress, and adjust your frequency to be constantly getting better.

What’s your experience with zone 2? Let me know in the comments!

Appendix: There Is No Precise Way to Enter Zone 2

Research suggests the precision of defining zone 2 is rather poor.

In a just-published paper, 30 male and 20 female cyclists with a mean age of 31 who had been cycling at least twice a week for at least three years underwent simultaneous testing of nine markers demarcating the boundaries of five different definitions of zone 2, all based on the five-zone model on which the popularity of zone 2 has grown. There are also three-zone models and seven-zone models. The very existence of 3, 5, and 7-zone models with five definitions for the single zone we are trying to target is sufficient to show this is a relatively nebulous concept.

The markers included four different lactate thresholds, two heart rate thresholds, ventilatory threshold one (the point at which the increase in breathing rate hits its first upward inflection in slope), 65% of peak oxygen uptake, and the point at which fatty acid oxidation is maximized.

The most precise relation between any two definitions of zone 2 was between percent maximal heart rate and lactate. But this was not very precise.

Based on one definition of zone 2, it occurs within a blood lactate of 1.5-2.5 mmol/L. An alternative or complimentary definition is 72-82% of maximum heart rate.

In a normally distributed bell curve, 95% of the data falls between 1.96 standard deviations above and below the mean. We can use the reported standard deviations to infer the probable range of the data. Since this is based on data from groups of people, we are assessing the utility of generalizing guidelines to be used by everyone, such as “you are in zone 2 when your lactate is between 1.5 and 2.5 mmol/L.”

These measurements represent the upper and lower bounds of zone 2 as well as its center:

At the lower bound with 1.5 mmol/L lactate, 95% of the time heart rate will be between 65 and 92% of maximum.

At the center with 2.0 mmol/L lactate, 95% of the time heart rate will be between 77 and 90% of maximum.

At the upper bound with 2.5 mmol/L lactate, 95% of the time heart rate will be between 80 and 92% of maximum.

The range of percent maximal heart rate found when lactate measurements indicate one is in zone 2 include 65-72%, which is considered zone 1, 82-87%, which is considered zone 3, and 87-92%, which is considered zone 4.

THIS IS FOUR OUT OF THE FIVE HEART RATE ZONES!

Sorry, but this means one of two things: either heart rate is useless or lactate is useless for defining zone 2. Certainly, they do not agree with each other.

Another lactate-based definition is that you have entered zone 2 when your lactate rises 0.5 mmol/L above baseline. In this study, people reached this value when they were between 75 and 87% of their maximal heart rate, which encapsulates both zones 2 and 3. While indicating only two of the heart rate zones instead of four, this is also a single value for lactate. Good luck keeping your lactate at exactly 1.5 mmol/L.

Now one thing we could conclude from this is that heart rate offers much more precision than lactate. After all, we can classify ourselves into four different heart rate zones within one lactate zone.

The problem is this: what is this supposed to be a proxy of?

In the 72-82% maximal heart rate definition of zone 2, 95% of VO2 estimates are between 38 and 86%. By VO2-based definitions, this includes all of zone 1, all of zone 2, and a little bit of zone 3.

At 65% of the peak VO2, one proposed floor of zone 2, 95% of heart rates are between 66 and 90% of maximum. This includes half of zone one, all of zones 1 and 2, and half of zone 4.

At the point of maximal fat oxidation, 95% of heart rates were between 61 and 83% of maximum, encapsulating all of zone 2 and most of zone 1.

At the first ventilatory threshold, 95% of heart rates were between 73 and 89%, covering most of zone 2, all of zone 3, and some of zone 4.

Thus, while percent of maximum heart rate seems more narrowly defined than lactate, if we try to pin down any one other zone 2 variable such as VO2, maximal fat oxidation, or ventilatory threshold, we wind up with a spread of multiple heart rate zones. And at the upper and lower bounds of the heart rate zones, we are covering parts of three VO2-based zones.

The overwhelming conclusion is that there is no precise definition to zone 2, so trying to chase it with precise data leads to a mirage: you cannot collect precise data about something that lacks precise definitions.

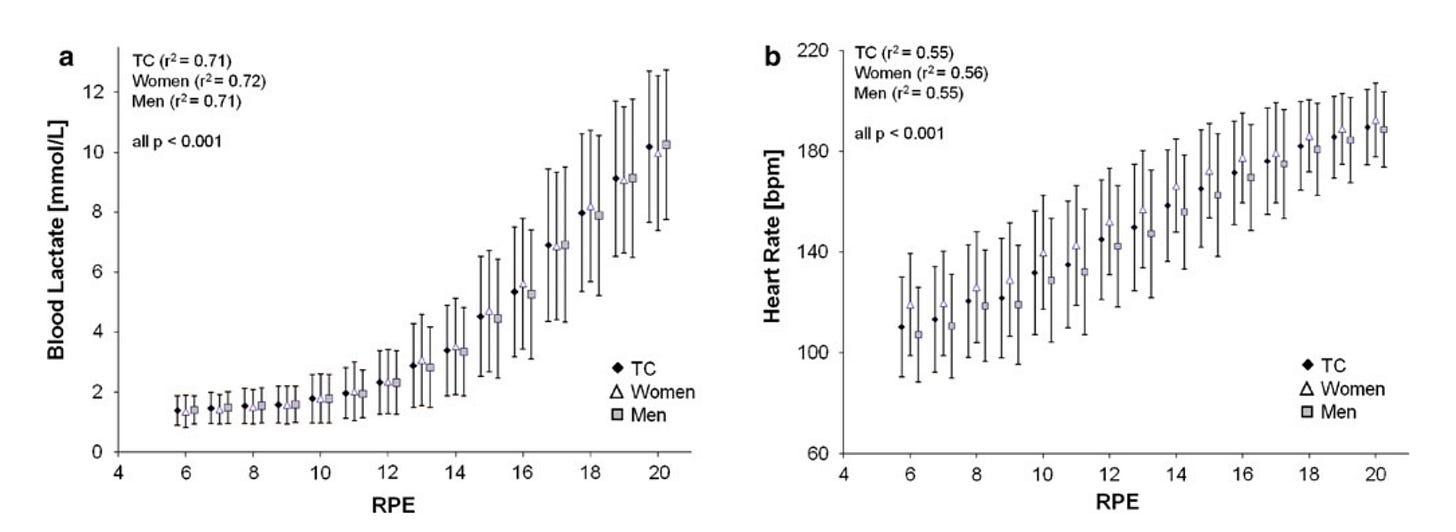

This paper did not cover the use of the rate of perceived exertion (RPE). However, a 2013 paper casts doubt on its ability to add any precision:

While RPE substantially correlates with both blood lactate and heart rate, the standard deviations are large. At an RPE of 6, 95% of blood lactates should fall within a 1.7 mmol/L range and 95% of heart rates fall within a 52-bpm range. At an RPE of 20, the heart rate spread falls to 44 bpm while the lactate spread increases to 10.3 mmol/L.

Even the tightest spreads around a single RPE are crossing multiple zones using any measured definition.

The talk test is a simple test of apparent exertion based on breathing labor. A 2015 paper subjected eight men and eight women with a mean age in their early 20s to an incremental exercise test where they repeated the pledge of allegiance and then answered whether they could speak comfortably. The speeds at which they last answered “yes, I can speak comfortably” (last positive, LP), “yes, I can speak, but not entirely comfortably” (equivocal, EQ), or “no, I cannot speak comfortably” (negative, NEG) were recorded. Then, they had to perform 30-minute bouts of steady-state exercise at each of those speeds.

An EQ rating seems to correlate with how people describe the relation of the talk test to zone 2. Perhaps the NEG represents the boundary of zone 3 by this method.

These authors do not state whether the error bars in their graphs are standard deviations or standard errors. Standard errors divide the standard deviation by the square root of the sample size (which in this case is 4). I cannot believe these are standard deviations because they are far smaller than any measurements I have seen in any other paper.

The error bars for heart rate correspond to about 2.7 bpm. If these are standard deviations this means 95% of the data would fall within a 10.5-bpm range, but if they are standard errors this indicates a standard deviation of 11 bpm and that 95% of the data would fall within a 43-bpm range. The mean heart rate itself travels upwards almost 30 bpm over 30 minutes, which indicates a more than 40-bpm range for the EQ speed if these are standard deviations and a more than 80-bpm range for the EQ speed if these are standard errors.

The mean lactate measurements themselves are completely outside of any definition of zone 2, which shows that the first perceptible increment on the talk test corresponds to a lactate reading ABOVE zone 2.

This itself suggests the talk test is not precise enough to set boundaries around zone 2 at all, never mind with precision.

The error bars on the lactate measurements represent about 0.65 mmol/L, but if these are standard errors the standard deviation would be 2.6 mmol/L. The mean lactate ranges from a little above 3 to a little above 4 over the course of the 30 minutes, which represents a 3.5 mmol/L spread if these are standard errors and a 11 mmol/L spread if they are standard deviations (which would mean the data would have to be skewed to the upside since the mean is much less than 11).

Thus, the talk test does not appear to register anything until lactate-based zone 2 boundaries are surpassed, and it does not seem to add any precision to the techniques covered above.

We could, of course, propose that repeated measures within an individual are much more useful than generalized boundaries derived from a sample of multiple individuals.

In 11 ballet participants who completed at least nine sessions in different heart rate zones, the intraindividual correlation coefficients between RPE and heart rate zones ranged from 0.57 to 0.96. The square of these represents the degree to which the heart rate zone explains the person’s RPE rating. This ranges from 32% to 92%. Whether some people are tremendously better at judging their own exertion than others, or whether this is trainable, is unclear. Obviously 92% is a very good ability to judge your zone based on your perceived exertion and 32% is a very bad ability.

In another study, eight recreationally active cyclists with at least two years of cycling experience underwent eight trials. The first two were used to determine the RPE at which exhaled carbon dioxide began increasing out of proportion to inhaled oxygen, indicating anaerobic metabolism spiking up and a second point 15% above this. The next six sessions had them try to maintain a steady state at one of these two RPEs.

At the first RPE, 95% of the heart rate measurements would be expected to range from 128 to 174 bpm; VO2 per kilogram bodyweight would range from 29 to 41, and lactate would range from 1.3 to 7.1 mmol/L.

At the second RPE, 95% of of the heart rate measurements would be expected to range from 148 to 183; VO2 would range from 34 to 44; and lactate would range from 2.3 to 9.8.

The heart rate spreads are crossing multiple zones and the lactate spread is simply crazy.

The authors’ objectives were to demonstrate the test-retest reliability of these measures. The CVs were below 5% for heart rate and VO2, which is considered a threshold for reliability, but were 9.2% and 12.7% for lactate, making lactate unreliable.

However, the objective was not to identify what zone anyone was in. Further, the CVs were based on the average of six measurements taken across 30 minutes, thereby collapsing the intra-session variability.

As quoted in a methods paper they cite, ‘‘there is literally no such thing as the reliability of a test, unqualified; the coefficient has meaning only when applied to specific populations.’’

So we can conclude that active cyclists who take at least five measurements during a 30-minute session can use RPE to predict heart rate and VO2, but not lactate, with reasonable reliability.

But that doesn’t mean they can use it to predict if they are in zone 2 by VO2-based, HR-based, or lactate-based definitions.

In conclusion:

Evidence suggests the talk test doesn’t start changing until zone 3 or higher.

Heart rate as a home measure is way easier to measure than lactate and appears to have much higher precision.

However, heart rate does not have anything remotely approaching single-zone precision based on any other metric. Thus, to be “precisely” in heart rate zone 2 does not necessarily put you in or near zone 2 according to any other physiological metrics, so it is not clear if you are in any specific “zone.”

Some people are good at judging their heart rate zone based on their perceived exertion and some people are horrible at it. It is unclear whether this is a trainable skill.

While I absolutely believe there is value to training different intensities, you have to consider classifying the intensity more of an art than a science. Trying to be highly precise about it is a waste of time and an exercise in conjuring fantasy.

Great article! I was raised in the 1980s ‘aerobic class’ era where ‘truly optimized’ aerobic activity was defined by the American Council on Exercise’s as involvement of all 5 major muscle groups simultaneously to produce best results.

Burpees, jumping jacks, rowing, bear crawls, etc.

I am retired so I have the time. I use the Morpheus system (Peter Attia interviewed the creator) which has only 3 zones. Zone 1 and 2 (blue zone) are compressed but users know the high end of the blue zone is more zone 2. The zone range changes based on recovery and resting heart rate for the day so it is a dynamic zone 2. I get my zone 2 via the rower but also walking after meals on a hill near my house. Average time is 30 minutes or so on those activities. Morpheus is a great system to track zone 2 or other zones.