In my last gluten post, I discussed why the ex vivo results of Dr. Fasano's 2006 study cannot logically be construed to show that gluten causes leaky gut in people without celiac disease, and why the available evidence suggests that people considered to have non-celiac gluten sensitivity do not have leaky gut.

Nevertheless, this study is a goldmine of valuable ideas that no one is touching.

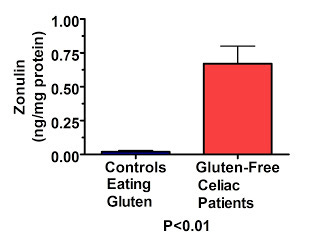

Not all of the study's results should be considered ex vivo. They took intestinal tissue from celiacs in remission and from non-celiac controls with digestive complaints, and measured the amount of zonulin in those tissues before performing any experiments on them.

Remarkably, they found that celiacs produce 30 times as much zonulin as non-celiacs, even though the non-celiacs were not eating gluten-free diets while the celiacs had been off gluten for over two years!

Here's a graph of their data:

This is remarkable because even though the point of the study was to show that gluten increases zonulin production, the controls were eating gluten yet had infinitesimal levels of zonulin production, while the celiacs had not eaten gluten for at least two years yet still had very high levels of zonulin production. This suggests that something besides gluten may be causing zonulin production in celiacs.

They found similar, though less dramatic, results for intestinal permeability:

Here they measured trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TEER) of intestinal tissue taken from gluten-free celiacs and gluten-eating controls. TEER is an estimation of the leakiness of the gut, where a lower value indicates a greater level of leakiness or permeability. They found that tissues taken from controls who had been eating gluten had three-fold less leakiness compared to celiacs who had been off gluten for over two years. This, again, suggests that something besides gluten may be contributing to leaky gut in people with celiac.

What is causing the persistently elevated zonulin in celiacs, or the somewhat less severe persistent elevation in gut permeability? It could just be that these subjects need to adhere to a gluten-free diet more strictly or for much longer than two years to fully resolve these issues. Or, it may be that certain types of intestinal dysbiosis (improper balance of bacteria and yeasts in the intestines) prime genetically susceptible individuals to develop celiac in response to gluten.

Dr. Fasano's group has also published a study showing that bacteria such as E. coli and Salmonella stimulate zonulin production in isolated intestinal tissue, and another recent study showed that short-term inoculation of rats with E. coli and Shigella enhanced the ability of gluten to cause intestinal damage while inoculation with Bifidus bacteria virtually eliminated gluten's ability to cause damage. Neither of these studies show that dysbiosis contributes to celiac, or that it is responsible for the persistence of zonulin production on a gluten-free diet, but they offer strong support to the plausibility of these hypotheses.

In any case, it is true that Dr. Fasano's 2006 study showed that gluten was capable of increasing zonulin and consequently increasing gut permeability ex vivo in intestinal tissue from both celiac and non-celiac subjects. Still, the effect in tissue taken from non-celiac individuals is pretty small.

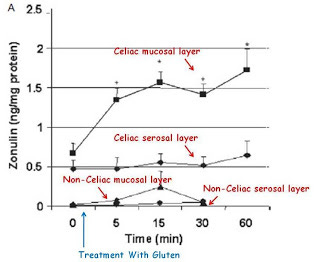

Here's the effect on zonulin:

Here they show that in the mucosal layer, but not the serosal layer, zonulin increases in response to gluten ex vivo, but that zonulin concentrations are dramatically higher in celiacs to begin with and remain dramatically lower in non-celiacs at all time points.

The mucosal layer is more superficial whereas the serosal layer is more deep.

Similar results were also seen for TEER, their estimation of gut integrity:

Here again we see that although gluten decreased gut integrity even in tissue isolated from subjects without celiac who were eating gluten as part of their normal diet, it never declined even close to the level seen in celiacs who had been gluten-free for two years.

As I pointed out in my last gluten post, these ex vivo experimental results showing that gluten proteins increase zonulin and leaky gut in isolated intestinal tissues cannot logically be construed as evidence that gluten causes leaky gut in live humans without celiac disease. There are far too many factors that could intervene in a live human to change the result. And indeed, Dr. Fasano's most recent study showing that people with non-celiac gluten sensitivity do not have leaky gut and the Australian study showing that gluten does not cause leaky gut in such individuals directly refute this concept.

Whether gluten contributes to the leaky gut seen in other diseases such as autism remains to be seen, but based on this data, one could could suggest that this is the case as a plausible hypothesis.

Ultimately, however, the most remarkable finding of this study is the massive persistence of zonulin production and leaky gut in celiacs even after they have been gluten-free for two years. The authors noted this in their conclusion:

Nevertheless, zonulin is markedly up-regulated in subjects affected by [celiac disease], even when treated with a gluten-free diet. This up-regulation is associated with increased baseline gut permeability, and an increased amplitude and duration of gluten-induced zonulin release when compared with non-[celiac disease] intestinal samples. Despite the presence of measurable zonulin response in both [celiac disease] and non-[celiac disease] subjects, [celiac disease] patients appear to reach a critical threshold of intestinal permeability upon gliadin exposure that is not reached in non-[celiac disease] intestinal mucosa.

This is remarkable because it suggests that celiac is about more than just genes and gluten. I will revisit this topic when I get my food toxins and food intolerances series going. In the mean time, I owe you all a sequel to my last LDL post, and then it'll be back to fructose for a while.