There seems to be a lot of confusion about the meaning of the term “lipid hypothesis” in pop science books, blogs, and other places.

Often times, the lipid hypothesis is confused with the diet-heart hypothesis. The two are very different. The lipid hypothesis concerns the role of lipids in the blood. The diet-heart hypothesis concerns the role of lipids in the diet.

The term “diet-heart,” as best as I can tell, was coined in the 1960s to describe the National Diet-Heart Study, which was designed to test the effect of reductions of dietary saturated fat and increases in dietary polyunsaturated fat on blood cholesterol and heart disease risk. In 1969, a panel of the American Medical Association headed by Edward Ahrens Jr. called this “the diet-heart question.”

In 1976, Ahrens first popularized* the term “lipid hypothesis” to refer specifically to the hypothesis that increased levels of cholesterol in the blood increase the risk for heart disease. He published a paper in the Annals of Internal Medicine entitled, “The Management of Hyperlipidemia: Whether, Rather than How.” Here's what he wrote:

What is The Lipid Hypothesis?

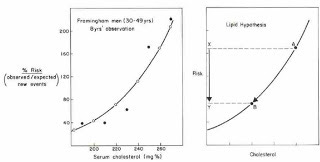

The Lipid Hypothesis is the postulate, based on Framingham (8) and similarly derived data, that reducing the level of plasma cholesterol in an individual or in a population group will lead to a reduction in the risk of suffering a new event of coronary heart disease. It is a premise based on the undisputed fact that people with higher plasma cholesterol levels have more and earlier coronary heart disease than do others with lower cholesterol levels; but the premise has not yet been proved true to the satisfaction of epidemiologists and biostatisticians or of the medical community at large. The Lipid Hypothesis, then, is simply an inference derived from accepted facts (Figure 1); though the hypothesis has been put to the test repeatedly in the past two decades, completely satisfactory evidence has not yet been advanced either pro or con.

His figure is meant to demonstrate the difference between association and causation:

On the left, we see the facts as they had been gathered at the time in Framingham, that blood cholesterol is correlated with the risk of heart disease. On the right we see a depiction of the hypothesis used to explain those facts. The arrow within the curved line represents a treatment used to lower the level of blood cholesterol. The arrow on the left side of the picture represents a hypothetical decrease in the risk of heart disease that results from the treatment. This hypothesis is the lipid hypothesis.

I have been writing about the need to distinguish between the lipid hypothesis and the diet-heart hypothesis for three years, since first reviewing Daniel Steinberg's The Cholesterol Wars (you can read my review here).

I credited Steinberg with making that proper distinction (indeed, I was not even aware of it until reading Steinberg's book), and criticized Uffe Ravnskov for conflating the two hypotheses in The Cholesterol Myths (you can read that review here).

I also emphasized this distinction in my last Wise Traditions lecture, “Heart Disease and Molecular Degeneration: The New Paradigm.”

Whether we view the lipid hypothesis as true, partly true, or false, I think it is important to make this distinction clear. The alternative is to jumble up various hypotheses and make it difficult to find the truth.

*I say “popularized” because Ahrens was not the first to use the term, even though this paper quickly became referenced as the first to define the lipid hypothesis. For example, see Epstein's 1977 paper, “Preventative trials and the diet-heart question: wait for results or act now.” Indeed, Ahrens' paper is the first indexed for pubmed that is searchable by the term “lipid hypothesis,” and appears to be the first paper ever written specifically devoted to defining the lipid hypothesis. However, Daniel Steinberg used the term in 1974 as a presentation to the Drugs Affecting Lipid Metabolism conference in Milan. Steinberg was the Chair of the planning committee for the Corornary Primary Prevention Trial, and described the committee as being charged to “to design a feasible study to test the ‘lipid hypothesis,' i.e., the hypothesis that intervention to reduce serum cholesterol levels does reduce risk of clinically manifest coronary artery disease.” Reference (provided by Dr. Steinberg): Steinberg, D. Planning the Type II Coronary Prevention Trial of the Lipid Research Clinics (U.S.A.) in Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 63: 417-426, 1975. Also cited as a book: (in) Lipids, Lipoproteins and Drugs (eds. D. Kritchevsky, R. Paoletti,and W.L. Holmes) Plenum Press, New York, 1975. Note that Steinberg's definition is the same as Ahrens'. It is possible that earlier print references exist; however, none appear to have popularized the definition until Ahrens' paper. The actual hypothesis, however, dates to Anitschkov's cholesterol-fed rabbit in 1913.